|

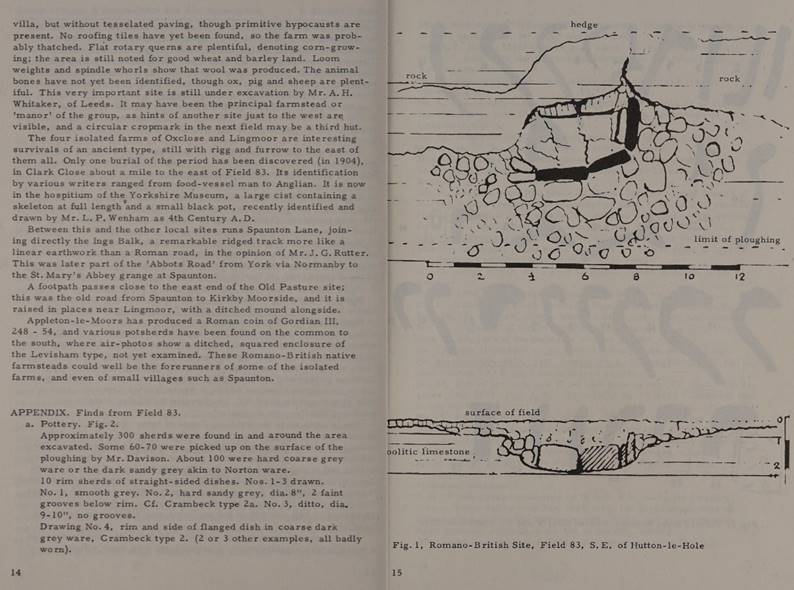

|

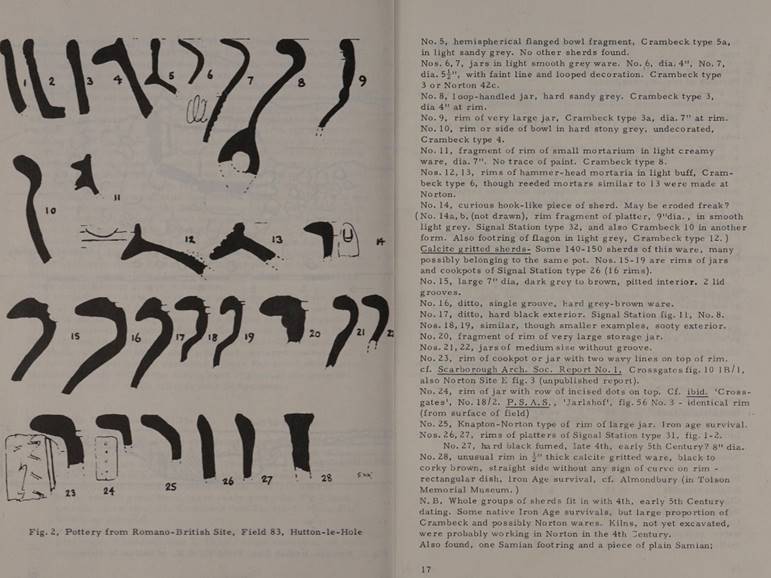

A Brief History of Time in the Ancestral lands around

Farndale A

journey back through time in the period before clear records of individual

Farndales |

|

Dates are in red.

Hyperlinks to other pages are in dark blue.

Royal dynasties are in blue

Headlines are in brown.

References and citations are in turquoise.

Local history of Farndale and its surrounding areas is in purple.

Geographical context is in green.

BCE - Before the common or current era. The contemporary

equivalent of BC.

CE - Common or current era.

The contemporary equivalent of AD.

kya

– abbreviation for a thousand years

YBP – Years before present

In contrast to other pages of this website, on this page we

travel backwards through time.

Introduction

We have explored the Farndale ancestry through

the clear and direct links provided by parish records and other sources to

about 1500, and then used medieval sources to find direct links to Doncaster at the time of the Black Death in

the fourteenth century. The medieval records have then provided some significant records of the

lives of our ancestors back to

about 1230. We have then explored

the cradle of the Farndale family, and the people who lived there, back to

the Norman Conquest.

We might imagine that those ancestral

individuals who must have lived in the dale of Farndale in the thirteenth

century, before leaving the dale but retaining its name, were in turn plucked

from the cauldron or primeval sludge of Bronze Age Beaker Folk, Iron Age

Settlers, Brigantes, Romans, Danes, Angles and Saxons that had roamed the moors

and dales of Yorkshire since about 9,000 years BCE.

So where did those more distant medieval

ancestors, who lived in Farndale, themselves come from? This page travels

backward in time from the Norman Conquest in 1066 to consider the evidence of

who our most distant ancestors may have been, roaming the area of the North

York Moors.

This webpage will work backwards through

the epochs of time as follows:

·

The early middle ages (866

CE to 1066). Saxon

and Norman England. Anglo Saxon England was arguably united as the Kingdom

of England by King

Æthelstan (927–939 AD), although the process was a long one. It

later became part of the short-lived North Sea Empire of Cnut

the Great, a personal union between England, Denmark and Norway in the 11th century. During this

period the majority of the Yorkshire population was engaged in small scale

farming. A growing number of families were living on the margin of subsistence

and some of these families turned to crafts and trade or industrial

occupations. In the 9th Century, the Vikings settled in many places all around

the North Yorkshire Moors, but there is no sign of them settling in the moors.

·

The post Roman period (410

CE to 866 CE). The

first written law codes, histories and literature emerged.

·

The Roman Period (70 CE to

410 CE). When

the Romans arrived in the area, they found organised resistance and strong

tribes prepared to fight for their land. The Romans came into the area further

east to patrol the coast. They built roads, part of which still exist and

warning stations on the cliffs at places like Huntcliffe. It is possible

that Roman patrols passed into the dales and even through Farndale,

but there is no evidence that they stopped there. A large fortification in

the location of modern day York was founded by the Romans as Eboracum in 71 CE.

The Emperors Hadrian, Septimius Severus, and Constantius I all held court in

York during their various campaigns. During

his stay 207–211 CE, the Emperor Severus proclaimed York capital of the

province of Britannia Inferior, and it is likely that it was he who granted

York the privileges of a 'colonia' or city.

·

The Iron Age (700 BCE to

70 CE). Iron

tools and weapons changed the fighting and working world, though dwellings and

lifestyles did not change significantly. Communities and tribes, although

warlike became more settled and cereal production and animal husbandry

increased. Iron Age farmsteads were made up of groups of small square or

rectangular fields and were often enclosed by low walls of gravel or stones.

Their huts were made of branches, or wattle and stood on low foundations of

stone. There was a massive hill fort at Roulston Scar, which dates back to

around 400 BC. It is the largest Iron Age fort of its kind in the north of

England. There are outlines of other such settlements near Grassington and

Malham. The most impressive Iron Age remains are at Stanwick, north of Richmond.

·

The Bronze Age (1800 BCE

to 700 BCE). The

Bronze Age was the period when metal ore was discovered. Copper was alloyed

with tin. By applying very high heat levels to ceramic crucibles it was

possible to alloy bronze and to caste axe heads, knives, spear heads, and

simple ornaments. This was the period represented by the Windy Pit discoveries,

including Beaker People pottery and human remains. The use of bronze was

probably introduced into Yorkshire by the Beaker Folk, who entered the area via

the Humber Estuary in about 1800 BCE.

·

The Neolithic Period, the New

Stone Age (3000 BCE to 1800 BCE). The New Stone Age was the period when tool making

skills produced stone axes, flint axes, arrow heads, spear points, fired clay

beakers and woven cloth. Neolithic society made pottery, weaved cloth and made

baskets. These people no longer lived a semi nomadic existence. Permanent

settlements were built, like to one at Ulrome, between Hornsea and Bridlington,

where a dwelling built on wooden piles on the shore of a shallow lake has been

found.

·

The Mesolithic Period

(9,500 to 3,000 BCE). The

Middle Stone Age was the period after the ice had receded. Microlith sites have

been found on the Moors including at Farndale,

including flint and stone chippings and tools. Early humans lived at Star Carr

which was first occupied in about 9,000 BCE.

·

The

last Ice Age dated from about 110,000 to 11,000 years ago. During that Ice Age

there were warm and cold fluctuations which lasted long enough to explain the

presence of sub tropical animals in Kirkdale cave.

·

The Palaeolithic Period or the Old Stone Age (10,000 BCE

to 2.6 million year ago). The Palaeolithic Period,

also known as the Old Stone Age, is a period in human prehistory

distinguished by the original development of stone tools. This period

covers about 99% of human technological prehistory. It extends

from the earliest known use of stone tools by hominids in Africa

about 3.3 million years ago, to the end of the Pleistocene.

Although this period covers human prehistory on a global scale, humans do not

appear to have emerged on the North Yorkshire Moors until about 9,000 BC,

during the Mesolithic Period.

The early middle

ages (1066 back to 866 CE)

The period from the Danish colonisation

of 866 AD to the

Battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066 was strongly influenced by Danish

colonisation, especially in the area of the Deiran and Bernician lands that

would merge into Northumbria. Viking

meant pirate or sea raider, but the English generally referred to them as

Danes.

1066

Edward the Confessor died in January

1066.

Tostig’s brother, Harold II (Harold Godwineson) (1066 to 1066) was elected king by the Witan, but

William I of Normandy claimed that Edward had promised the throne to him. In

the context of a power struggle, Harold was then faced with a combined threat

from a reinvasion by the Danes and from the Normans.

Tostig had fled to Flanders and had

gathered a fleet of 60 ships. He entered Lincolnshire but was driven out and

fled to Scotland with only 12 ships. Harld Hardrada, King of Norway accepted

the exiled Tostig as allies and they sailed up the Humber and Ouse with 300

ships.

The Danes, led by the

Norwegian King Harold Hardrada, sailed up the Ouse, with support from Tostig

Godwinson and after the Battle of Fulford, they seized York. Harold then

marched his army north to York (185 miles) in four days and took the invaders

by surprise. They were defeated at the Battle of Stamford Bridge (some 10km

east of York) in which Harold Hardrada and Tostig were killed.

There is an In

Our Time podcast on the

Battle of Stamford Bridge, the decisive English victory over Viking forces

which took place in September 1066.

However Harold was then required to rush

south again, with so much of his exhausted army as could keep up, to face

William I at the Battle of Hastings.

1063

Earl Tostig had the supporters of his

rival, Gospatrick of Bamburgh – Gamal son of Orm, and Ulf son of Dolfin, killed in

York in 1063.

Tostig then sought to increase taxation

which prompted opposition. The Northumberland folk revolted in 1065 and marched

on York and Tostig’s Danish housecarfs (a force of about 200) were destroyed

near the Humber. Tostig was outlawed.

1055

The beautiful Saxon Church

of Kirkdale lies about a mile west of

Kirkbymoorside, south of the North York Moors, and overlooks the Hodge Beck.

Within the porch at the entrance door is housed a Yorkshire treasure. It is a

Saxon sundial, and it bears the inscription “Orm the son of Gamel acquired

St Gregory’s Church when it was completely ruined and collapsed, and he had it

built anew from the ground to Christ and to St Gregory in the days of King

Edward and in the days of Earl Tostig”. The inscription refers to Edward

the Confessor and to Tostig, the son of Earl Godwin of Wessex and brother of

Harold II, the last Anglo Saxon King of England. Tostig was the Earl of

Northumbria between 1055 and 1065. It was therefore during that last peaceful

decade, immediately before the Norman conquest, that Orm, son of Gamel rebuilt

St Gregory’s Church.

The Domesday book

evidences that Kirkdale by about this time comprised ten villagers, one priest,

two ploughlands, two lord’s plough teams, three men’s plough teams, a mill and

a church. Orm

seems to have held five carucates of land at Chirchebi. So presumably this area

of land described the five carucates of cultivated land around Kirkdale.

Siward

died in 1055, leaving one son, Waltheof. He was buried at St Olave’s Church,

which he had built, just north of York’s walled boundary.

Siward’s son, Waltheof was too young to

become Earl of Northumbria. King Edward chose Tostig, son of Earl Godwin of

Wessex to succeed Siward.

1053

Harold Godwineson became earl of Wessex.

The Godwines by now were largely running the country.

By this time York had seven

administrative districts, with one controlled by the Archbishop. The townsmen

had extensive pasture rights in the surrounding area. Archaeology has revealed

significant manufacturing in metal, glass, amber, jet, deer horn, wood and

bone.

Local

organisation focused around a lord’s great hall (later called manors by the

Normans). From these would satellite outlying demesne farms which were called berewicks.

Free men held soke estates. There were some larger sokes which

belonged to the King, church or Earl. In other words, there was an informal

hierarchy from larger to smaller lordships. (John

Rushton, The History of Ryedale, 2003, 23).

Over seventy thegns are listed in the

Domesday Book, including the large landowner Ormr, who held Kirkbymoorside,

Earl Siward, Gamal, Tosti and Ughtred of Cleveland.

Arable farming focused around vills

or towns.

Tax was assessed on cultivated land

through caracutes (derived from the Latin carruca, plough) and bovates.

Early assessments were therefore focused on the amount of ploughing that could

be achieved in an area of land. These initial measures would last through time,

even though methods of ploughing changed. A carucate was a medieval land unit

based on the land which eight oxen could till in a year.

The dales flowing down from the moorland

remained thinly settled.

It is not clear how strongly held

Christian belief were at a local level. Many pagan customs continue. The days

Tuesday through to Friday are still named after Anglian and Norse Gods. Hills

remained dedicated to the Norse Gods Odin and Woden, Much Yorkshire folklore

remains rooted in Anglian and Norse traditions. Hobs and boggles remained in field

names. However masonry at churches evidences Christian assimilation. The

settlement at Chirchebi that would be the burgeoning lands of

Kirkbymoorside was a small rural community focused around the church of St

Gregory and its priest. The eleventh century sundial at Kirkdale is the best

preserved of several including others at Edstone and Old Byland.

1051

The rivalry between the Godwine family

and the Normans started to bubble over. There was a violent dispute in Dover

between Normans and the locals. The Godwines were ordered by the King to punish

the Dover folk, but they refused. They were outlawed and exiled, but they were

sufficiently powerful that Edward was persuaded to reconciliation.

1050

According to William, Duke of Normandy, Edward

named William as Edward’s successor to the English crown.

There was a succession battle waiting to

happen:

·

Cnut’s

heirs were waiting in the wings.

·

The

Godwine family, vast landowners and now married in to the royal family, were

staking their claim.

·

William

of Normandy had also staked his claim.

1044

Edward the Confessor married Edith,

daughter of Earl Godwine. They had no children.

1042

Edward

“the Confessor” (1042 to 1066) restored the

House of Wessex to the English throne. He became king in 1042 as Aethelred’s

surviving son, Cnut’s sons having died early. He is remembered for his deep

piety which led to his focus on the building of Westminster Abbey while the

country was generally run by Earl Godwin and Harold.

By this time many of the names of towns

and places were of Viking origin, such as those ending in by or thorp.

However the old Anglo Saxon names

remained abundant suggesting an assimilation during the Viking times rather

than a period of ethnic cleansing. Scandinavian language

survived widely in the countryside.

1040

Harthacanute

(1040 to 1042)

was the son of Cnut and

Emma of Normandy was quickly accepted as king as he sailed to England with a

fleet of 62 ships. He died at the age of 24 at a wedding when toasting the

health of the bride. He was the last Danish King of England.

1035

Harold

I (Harold Harefoot) (1035 to 1040) was Cnut’s

‘illegitimate’ son claimed the throne while his brother Harthacanute was in

Scandinavia, but died before Harthacanute needed to invade to retake the

throne.

1033

Cnut chose a

fellow Dane, Siward, as his Yorkshire Earl.

1030

The Horn of

Ulph is an eleventh-century oliphant (a horn carved from an elephant's

tusk). It is two feet four inches long, and has a diameter at the mouth of five

inches. Given its size and condition, it is a particularly good example of a

medieval oliphant. Tradition holds that it is a horn of tenure, presented to

York Minster by a Norse nobleman named Ulph sometime around 1030. This suggests

that a powerful Scandinavian nobleman was willing to donate a very valuable

object to the Christian church by this time.

1016

Edmund

II “Ironside” (1016 to 1016),

was chosen by the folk of London as Aethelred’s successor but the King’s

Council, the Witan, chose Cnut. Ironside denoted Edmunds strength and

endurance in battle, but Edmund was defeated at the Battle of Assandun and made

a treaty with Cnut for a form of power sharing until he was assassinated.

Cnut

(or Canute) “the Dane” (1016 to 1035) then became

king of a united England, divided into four earldoms of East Anglia, Mercia,

Northumbria and Wessex. Siward of Northumbria appeared in Shakespeare’s

Macbeth. Leofric, Earl of Mercia was married to Lady Godiva who rode naked

through Coventry to persuade him not to impose a tax increase. There is an In Our Time podcast on Cnut.

In an attempt to reassure the indigenous

population, he married the widow of Aethelred II, Emma of Normandy and he

recognised the limitations of his powers in the famous scene when he ordered

the tide not to come in, in the knowledge that he would not succeed.

About 130 years into the birth of the

English nation, she had become a part of the North Sea empire.

1013

By 1013 he had fled to Normandy after

the Danish King Sweyn Forkbeard had invaded the burgeoning English lands from

1013 on the pretext of a massacre of Danes living in England on St Brice’s Day.

Sweyn had come up the Humber that year.

Sweyn was pronounced King of England on 25

December 1013, but died 5 days later.

Aethelred returned to England but spent his remaining years at war with

Sweyn’s son, Cnut.

1000

By about 1000, the lands were commonly

referred to as Engalond, of various spellings.

991 CE

The renewal of Danish attacks on

southern England from 975 CE led to the payment of a regular tribute, the

Danegeld from 991 CE.

Aethelred made a fateful treaty in 991

CE with Richard , Duke of Normandy. In the same year a fleet led by King Olaf

Tryggvason of Norway led to the death of his ealdorman Byrhtnoth at Maldon in

Essex. After Maldon, Aethelred raised he sums by a universal land trax to bribe

the Danes, known as the Danegeld. The weight of taxation drove the peasantry to

servitude. Rudyard Kipling later lamented

that once you have paid him the Dane geld, you never get rid of the Dane.

There is an In

Our Time podcast on the

Danelaw.

Yorkshire had a Danish

leadership who were unwilling to fight other Danes and there was less trouble

there.

978 CE

Aethelred

II “The Unready” (978 to 1016 CE) failed in the

ongoing resistance against the Danes. He was dubbed unready from unraed

or ill advised.

975 CE

Edward

the Martyr (975 to 978 CE) became king

at the age of 12 and was the victim of a family power struggle until his murder

by his stepmother at Corfe Castle.

959 CE

Edgar

(959 to 975 CE)

met the “six kings of

England” and gained their allegiance at Chester, including from the King of

Scots, the King of Strathclyde and various Welsh princes. Edgar imposed lighter taxation and allowed

greater autonomy across the area of modern Yorkshire, which became assimilated

into the wider English Kingdom.

York remained the only sizeable town and

became a centre for craftsmen and merchants. The town had a level of self

government under the hold or High Reeve.

The wider district started to take its

name after the town of York. The Shire started to recognise three Ridings,

which were themselves divided into some 28 wapentakes (perhaps named after the

brandishing of weapons at gatherings to show approval). Often the waopentakes

were named after their meeting places at hills, burial mounds, crosses or

trees.

The land of St Cuthbert at Durham

retained a separate identity.

For a period there were no invasions.

Dunstan, the Archbishop of Canterbury increased the power and the wealth of the

monasteries.

By about this time:

·

Agriculture

started to prosper.

·

Law

enforcement was generally conducted at a local level. Men were divided into

tithings or groups of ten men, to look out for each other, and bonded together

through feasting and drinking together. Ten tithings would form small units to

chase rustlers and bandits.

·

A

relatively homogenous form of customary law emerged.

·

There

was an English church and English saints.

·

A

wide coinage was in circulation with the King’s head.

·

An

administrative system emerged based upon the scir or shire, governed on behalf

of the king by an ealdorman and his deputy or scirgerefa (sheriff).

·

Significant

numbers came to be involved in the administration of the kingdom, including the

collection of tax.

·

The

people of the kingdom were given a form of representation by gatherings of

thegns and prelates who became councillors of the witan who were summoned from

time to time by the king.

·

The

export of wool became a mainstay.

·

Roads,

bridges and harbours were maintained publicly.

The new kingdom was

perhaps one of the stablest and richest lands amongst the European states.

However its fragile process for the succession of kings (by a mix of

inheritance, bequest and election) was a weakness which would dominate the

following century.

955 CE

Eadwig (955 to 959 CE) was a

teenage king who was perhaps best remembered for being late for his coronation

after sleeping in.

954 CE

Then, in 954 CE, King Eric

I of Norway of the Fairhair dynasty (Eric Haraldson known as Eric Bloodaxe) was

slain at the Battle of Stainmore by King Eadred who retook the city at Jorvik

and completed the unification of England.

946 CE

Eadred (946 to 955 CE) continued

to resist the Danes.

939 CE

Edmund (939 to 946 CE) became king

at the age of 18, having fought with his half brother at the Battle of

Brunanburh. He consolidated Anglo Saxon control over northern England.

937 CE

The Norse-Gaels, Ostmen or

Gallgaidhill became Kings of Jorvik after long contests with the Danes over

controlling the Isle of Man, which prompted the Battle of Brunanburh. After his

victory against an invading army of Irish Vikings, Scots and Britons at

Brunanburh. Aethelstan was proclaimed rex Anglorum, king of the English.

In one of the bloodiest battles faught in Britain, Aethelstan defeated a

combined army of Danes and Vikings, Scots and Celts. The battle meant that for

the first time the Anglo Saxon kingdoms were brought together to establish a

unified England.

927 CE

Aethelstan

defeated the Vikings at York and

there was peace until 934 CE.

There is an In Our Time podcast on the reign of King Athelstan, whose

military exploits united much of England, Scotland and Wales under one ruler

for the first time.

The Vale

of York Hoard, also known as the Harrogate Hoard and the Vale of York

Viking Hoard, is a 10th-century Viking hoard of 617 silver coins and 65 other

items. It was found undisturbed in 2007 near Harrogate. It was deposited in

about the period 927 to 927 CE.

924 CE

Aethelstan (924 to 939 CE) extended

the boundaries of the Anglo Saxon lands.

920 CE

All the rulers in Britain

submitted to Edward the Eler as father and lord.

899 CE

Edward the Elder (899 to 924 CE) retook the

south east from the Danes up to the Humber and united Mercia with Wessex.

However there were multiple Danish invasions including from Ireland and

Scandinavia. Edward was killed fighting the Welsh at Chester.

The Swedish Munsö dynasty became overlords of Jorvik because the Danes in

Britain had promised loyalty to the Munsö Kings of Dublin, but this dynasty was

focused on the Baltic Sea economy and quarrelled with the native Danish Jelling

dynasty (which originated in the Danelaw with Guthrum).

890 CE

In the late 9th century

Jorvik was ruled by the Christian King Guthfrith. It was under the Danes that the ridings and wapentakes of Yorkshire and the Five

Burghs were established. The ridings were arranged so that their

boundaries met at Jorvik, which was the administrative and commercial centre of

the region.

886 CE

Alfred seized London and the Anglo Saxon

Chronicle wrote that all the English race turned to him. This might be taken to

be the birth of the English nation, but not yet the mark of a united English

kingdom. Alfred was perhaps the first king who might have been believed to be

king of Angelcynn and defender of the eard (the land). Yet the English

were not yet a nation.

866 CE

Aethelred I (866 to 871 CE) struggled

with the Danes throughout his reign who started to threaten Wessex itself.

In 866 CE,

when Northumbria was internally divided, the Vikings captured York. The

Danes changed the Old English name for York from Eoforwic,

to Jorvik. The Vikings destroyed all the early monasteries in the area

and took the monastic estates for themselves. Some of the minster churches

survived the plundering and eventually the Danish leaders were converted to

Christianity. Jorvik became the Viking capital of its British lands and it

would reach a population of 10,000. Jorvik became an important economic and

trade centre for the Danes. Saint Olave's Church in York is a testament to the

Norwegian influence in the area. Jorvik perhaps prospered from its trade with

Scandinavia.

Genetic mapping indicates

that whilst Norwegian DNA is still detectable in northern groups, especially in

Orkney, no genetic cluster in England corresponds to the areas that were under

Danish control for two centuries. The Danes were highly influential militarily,

politically and culturally but may have settled in numbers that were too modest

to have a clear genetic impact on the population.

879 CE

In 879 Alfred summoned his army to meet

at Ecgberht’s Stone and they were joined by the folk of Somerset and Wiltshire,

hey attacked the Danes at Ethandun (Edington) and defeated the Danes who agreed

to be baptised.

875 CE

In 875 CE, Guthrum became leader of the

Danes and he apportioned lands to his followers. Most of the indigenous

population were allowed to retain their lands under the lordship of their

Scandinavian conquerors. Ivar the Boneless became "King of all Scandinavians

in the British Isles".

871 CE

Alfred the Great (871 to 899 CE) has been

remembered in history as educated and practical, a Christian philosopher king. After

some initial success against the Danes under Guthrum, the Danish king of East

Anglia, the Danes launched a counter attack and Alfred famously retreated to

the marshland of Athelney in the Somerset levels to regroup. He established

Christian rule over Essex and then more widely across the Anglo Saxon Kingdoms.

He founded a permanent army and a small navy. He began the Anglo Saxon

chronicles.

There is an In Our Time podcast on King Alfred and the defeat

of the Vikings at Battle of Edington and Alfred's project to create a culture

of Englishness.

865 CE

By 865 CE a great heathen

horde (a micel here) attacked in East Anglia and began to challenge the

political balance of the Anglo Saxon Kingdoms. Large mobile encampments arose

across the land, including at Aldwark near York.

858 CE

Aethelbald (858 to 860 CE) was the

second son of Aethelwulf.

Aethelbert (860 to 866 CE) witnessed

the sacking of Winchester by the Danes, although the attackers were then

defeated.

850 CE

After 850 CE, Viking raiding parties

started to camp through the winter. They started to obtain horses and became

more mobile.

839 CE

Aethelwulf

(839 to 858 CE)

was King of Wessex and

father of Alfred. He defeated a Danish army at Oakley.

By the mid ninth century there was an

increasing influence of Scandinavian culture including upon the language. Many

words of modern use in northern dialect have Norse origins, including dale

(from the the Norwegian ‘dalr’, valley), beck (stream) and fell

(mountain).

835 CE

Opportunistic raids by Viking warrior

seamen continued over the next half century. By 835 larger Viking fleets began

to engage in more significant confrontations with royal armies.

The effects of Viking raids on the

indigenous peasant population, who were exposed to violence and enslavement,

must have been profound. The impact was also political as warlords sometimes

made alliances with the Danes, or were forced to resist them.

827 CE

Egbert

(827 to 839 CE) was the

first Saxon King to establish relatively stable rule across Anglo Saxon

England.

793 CE

The first known Viking raid on the

British Isles was the assault on Lindisfarne off the modern Northumbrian coast

in 793 CE. The Anglo Saxon Chronicle and accounts by

Alciun in the Frankish Kingdom of Charlemagne describe a violent a bloody

scene.

On 8 June 793 Vikings raided Lindisfarne,

their first attack on the British Isles. The raid was devastating for the

community of Lindisfarne, but had ominous implications

for the wider religious and political world. By 875 CE monks at Lindisfarne

decided to leave and they took St Cuthbert’s coffin with them to Chester le

Street and then to Durham.

Viking Raiders, ‘Judgement Day” Stone, c800 to 825 CE – a procession of

seven men, six armed with swords and axes.

At that time, there was no united

kingdom called England. Instead there were smaller kingdoms dominated by Wessex

in the south west, Mercia in the Midlands, East Anglia in the eastern fenlands,

and Northumbria in the north, with which we are most interested. These kingdoms

had evolved out of the chaos after the withdrawal of the Romans from Britain.

They are often collectively referred to as Anglo Saxon kingdoms.

The post Roman

period (866 CE back to 410 CE)

During the period 410 to

866 CE, Angle and Saxon farmers settled in the dales and small villages started

to emerge.

The town at

the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss, today known as York, had

developed from Roman Eboracum, following a period of decline, to a settlement

of the Angles by the fifth century CE. By the seventh century CE, Eoforwic

was the chief city of King Edwin of Northumbria. The first wooden monster

church was built in Eoforwic in 627 CE for Edwin’s baptism. After 633 CE

the wooden church was rebuilt in stone. In the eight century CE Alcuin of

Eoforwic was at the centre of a Cathedral school.

There is a separate page

on Alcuin

of York.

The area of Farndale has been described as and area stretching, ‘northwards

from the Wolds, of windswept moors of Hambleton and Cleveland (Cliffland) and

still remain much as they were in pre-historic times. A refuge of broken

peoples, a home of lost causes.’ Bede described the area as ‘vel bestiae commorari vel hommines bestialiter vivre conserverant.’

(A land fit only for wild beasts and men who live like wild beasts). When the

Romans left the Saxons in very small numbers did venture into the dales on the

moors and left their burial mounds and stone crosses on the high ground and

these can still be seen. Thus the people who today come from the

dales of the North Yorkshire Moors were a relatively isolated population for

several hundred years and they had developed very special characteristics. In

many respects, this has provided a uniqueness.

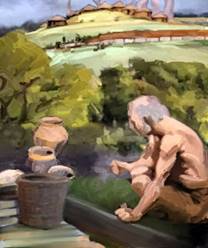

Diet

In Northumbria from about

500 CE, the diet of the folk who lived in Anglo Saxon Britain was likely based

on cereals, bread and porridge with vegetables including onions and leaks,.

Peas and white carrots. Meat was eaten very rarely and fish was caught in

rivers. Hunting was a sport of nobles and wild boar and deer might have been

taken from time to time. Food would have been cooked at an open fire in the

middle of a dwelling in a large iron pot hung over the fire. Bread might have

been baked in clay or stone ovens outside.

731 CE

The Venerable Bede (672 or 673 to 26 May 735) (“Saint Bede”) was an English monk and an author and scholar who wrote the

Ecclesiastical History of the English People which he completed in

about 731 CE. He was one of the greatest teachers and writers during the Early

Middle Ages, and is sometimes called "The Father of English History".

He served at the monastery of St Peter and its

companion monastery of St Paul at Monkwearmouth and Jarrow in the Anglian

Kingdom of Northumbria.

The Life of

the Venerable Bede, on the state of Britain in the seventh century,

begins: In the seventh century of the Christian era, seven Saxon kingdoms

had for some time existed in Britain. Northumbria or Northumberland, the

largest of these, consisted of the two districts Deira and Bernicia, which had

recently been united by Oswald King of Bernicia ... The place of his birth is

said by Bede himself to have been in the territory afterwards belonging to the

twin monasteries of Saint Peter and Saint Paul at Weremouth and Jarrow. The

whole of this district, lying along the coast near the mouths of the rivers

Tyne and Weir, was granted to Abbot Benedict by King Egfrid two years after the

birth of the Bede.... Britain, which some writers have called another world,

because from its lying at a distance it has been overlooked by most

geographers, contained in its remotest parts a place on the borders of

Scotland, where Bede was born and educated. The whole country was formed

formerly studded with monasteries, and beautiful cities founded therein by the

Romans, but now, owing to the devastations of the Danes and Normans, has

nothing to allure the senses. Through it runs the Were, a river of no mean

width, and of tolerable rapidity. It flows into the sea and receives ships,

which are driven thither by the wind, into its tranquil bosom. A certain

Benedict built churches on its banks, and founded there two monasteries, named

after St Peter and St Paul, and united together by the same rule and bond of

brotherly love.

Bede gave intellectual and religious

significance to as burgeoning nation at Jarrow from where many centuries later John William

Farndale was the youngest member of the Jarrow marchers. Bede first defined

an English identity. Bede produced the greatest volume and quantity of writing

in the western world of his time. At his monastery at Jarrow he had access to a

university library with more books than were in the libraries of Oxford or

Cambridge 700 years later. (Robert Tombs, The

English and their History, 2023, 24, 26).

685 CE

By about 685

CE, the early church at Kirkdale was dedicated

to St Gregory. There are two elegant tomb stones within its grounds which are

once said to have borne the name of King Oethelwald. More recent excavations

tend to suggest that the church at Kirkdale was important.

The origin of

parish churches emerged at about this time. A parish was a district that

supported a church by payment of tithes in return for spiritual services. Some

churches were linked to manor houses and others originated as the districts of

missioning monasteries. The church at Whitby was

near a major settlement, whilst the church of St Gregory’s at Kirkdale was

located remotely in a dale. By 1145, Kirkdale was described as the church of

Welburn. Recent excavations tend to confirm the view that an important church

was at Kirkdale (John Rushton, The

History of Ryedale, 2003, 19).

In

contrast to the trackless moorland wilderness haunted by wild beasts and

outlaws where Lastingham was built, in Kirkdale, an ancient route from north to

south descended out of Bransdale to form a crossroads with an ancient route

from west to east along the southern edge of the moors. Travellers needed

shelter, medical attention and perhaps spiritual sustenance. It may well have

been to provide these Christian ministrations and to teach the gospel in the

region that a small community of monks was established there as a minster

(Latin monasterium) dedicated to Gregory the Great, English Apostle. It

has been speculated that the original settlement in Kirkdale was an early

offshoot of Lastingham. Inside the Minster, two finely decorated stone tomb

covers, generally agreed to date from the eighth century, hint that this early

church had wealthy patrons - perhaps royal patrons at least one of whom may

have been venerated in Kirkdale as a saint.

We

don't know exactly when the first church was built at Kirkdale. It may have

been a daughter house of the monastic community at nearby Lastingham, which was

founded in AD 659. The first church at Kirkdale was a minster, or mother church

for the region. It may have included a chancel - a rarity for Anglo-Saxon

churches. Surviving from that early building are two

finely carved 8th-century stone grave covers inside the church. The quality of

the carving suggests that the church had wealthy patrons, perhaps of a locally

royal family. The Friends of

St Gregory's Minster Kirkdale suggest that at least one of these

8th-century patrons may have been venerated locally as a saint. There are also

three fragments of Anglo-Saxon cross shafts built into the church walls. These

cross shafts date to the 9th and 10th centuries.

Pope

Gregory (St Gregory) sent St Augustine on his mission to convert the English to

Christianity in AD 597 (see below). The Minster is dedicated to him.

It

seems likely that the minster fell into ruin, perhaps as a result of Danish

raids. We know that the church was rebuilt around 1055 because of the clue in

the sundial (see further above).

Pope Gregory had

encouraged the conversion of pagan holy places to Christianity and the church

at Kirkbymoorside is near a large burial mound.

670 CE

In the 670s Cuthbert, said

to have been inspired by a vision of Aidan’s death to have joined to

monasteries at Ripon and then Melrose, joined Lindisfarne as prior and became 7th

Bishop of Lindisfarne in about 685 CE. He aimed to reform the monk’s way of

life in compliance with the religious practices of Rome, rather than Ireland.

He later became a hermit on St Cuthbert’s island and

later on Inne Farne. He died on 20 March 687 and is

buried inside he church at

Lindisfarne.

Bishop Eadrith

(died in 721 CE) later commissioned Bede to write the Life of Saint Cuthbert.

In about 700 CE Eadrith also created the illuminated manuscript

Lindisfarne Gospels, in

honour of St Cuthbert. Bishop Aethelwold of Lindisfarne bound it and Billfrith

created a jewelled metalwork cover. The manuscript combined influences from

Mediterranean, Irish and Anglo Saxon traditions.

There

was for a time some disagreement between the Roman and Lindisfarne missions.

This caused conflict within the church until the issue was resolved at the Synod of Whitby in 663 by Oswiu of Northumbria opting

to adopt the Roman system.

The

schism had come about because the church in the south were tied to Rome, but

the northern church had become increasingly influenced by the doctrines from

Iona. The Synod was held in the monastery at Streoneschalch near to Whitby.

659 CE

Christianity in Ryedale

and the stone crosses of the Ryedale School

Many local churches in

Ryedale date back to the Anglo-Saxon period. The churches are not the earliest

evidence of the arrival of Christianity to the north of England. The first

evidence was the establishment of a chain of monastic sites from Lindisfarne down

the coast to Whitby,

their influence then extending inland to Crayke, Lastingham and Hackness. The

Venerable Bede recorded that in 659 CE the monk Cedd hallowed an inauspicious

site at Lastingham and established there the religious observances of

Lindisfarne where he had been brought up. By the time Bede was writing in circa

730 CE, there was a stone church at Lastingham.

Christianity was spread

through the work of missionaries who travelled the countryside, often erecting

preaching crosses. They were originally made of wood, but with the re

introduction of building in stone, stone crosses became the norm. These

preaching crosses depicted scenes from the Bible and were often elaborately

decorated with motifs from the Mediterranean. The carvings may have originally

been painted in bright colours. In the central part of Ryedale there were local

Craftsman who produced such crosses which were unique in their design. A

typical Ryedale School cross was about 6 feet tall with a slightly tapering,

flat, oblong section shaft. The style occurs in Kirkbymoorside, Levisham and

Middleton. The Ryedale dragon is an ornamentation on the back panel of the

cross shaft. A single beast, often in an S shape, filled the whole panel.

There is an In

Our Time podcast on the Celts.

Bede,

in his History of the English Church and People (731

CE), records that in 659 CE, a small monastic community was planted at

Lastingham under royal patronage, partly to prepare an eventual burial place

for Æthelwald, Christian king of Deira, partly to assert the presence and

lordship of Christ in a trackless moorland wilderness haunted by wild beasts

and outlaws.

Chap.

XXIII. How Bishop Cedd, having a place for building a monastery given him by

King Ethelwald, consecrated it to the Lord with prayer and fasting; and

concerning his death. [659-664 a.d.] The same man of God, whilst he was bishop

among the East Saxons, was also wont oftentimes to visit his own province,

Northumbria, for the purpose of exhortation. Oidilwald,425 the son of King

Oswald, who reigned among the Deiri, finding him a holy, wise, and good man,

desired him to accept some land whereon to build a monastery, to which the

king himself might frequently resort, to pray to the Lord and hear the

Word, and where he might be buried when he died; for he believed

faithfully that he should receive much benefit from the daily prayers of those

who were to serve the Lord in that place. The king had before with him a

brother of the same bishop, called Caelin, a man no less devoted to God, who,

being a priest, was wont to administer to him and his house the Word and the

Sacraments of the faith; by whose means he chiefly came to know and love the

bishop. So then, complying with the king's desires, the Bishop chose himself

a place whereon to build a monastery among steep and distant mountains,

which looked more like lurking-places for robbers and dens of wild beasts,

than dwellings of men; to the end that, according to the prophecy of

Isaiah, “In the habitation of dragons, where each lay, might be grass with

reeds and rushes;”426 that is, that the fruits of good works should spring up,

where before beasts were wont to dwell, or men to live after the manner of

beasts.

650 CE

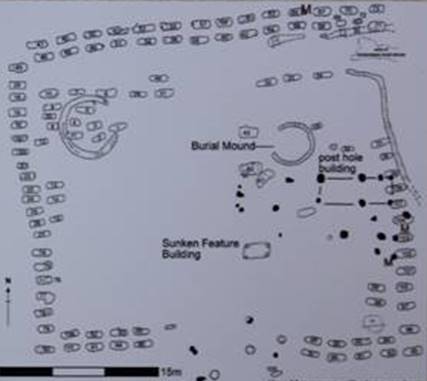

An

aristocratic burial ground at Street House near

Loftus and Carlin How, dates to

about 650 CE, a period of transition from paganism to Christianity in England.

The cemetery was superimposed on a prehistoric monument and contained a high

ranking woman on a bed surrounded by 109 graves, arranged two by two. The

location would have been just within the northern border of Deira. The royal

princess watched over Carlin

How

(“the hill of witches”) for thirteen centuries

until she was excavated in 2005 to 2007.

The cemetery was only used

for a short period of time. The cemetery is focused on one burial near the

centre of the cemetery, known as grave 42. The objects from this grave were the

first indication to archaeologists that this was an important person. The grave

contained three gold pendants, each one unique in northern England. The female

had been placed on a wooden bed with iron fittings and decoration. Bed burials

are very rare and had only been found previously in southern England.

There are only a small

number of bed burials in England including two at the royal cemetery at Sutton

Hoo in Suffolk. The bed was placed in a chambered tomb with a low mound marking

the site of the grave. Other graves define the extent of the burial area as an

irregular square 36 metres by 34 metres. There are two buildings within the

cemetery, one possibly a mortuary house where the princess from grave 42 may

have been laid prior to her burial. The cemetery was created within an earlier

Iron Age enclosure dating to about 200 CE and the link to the past may have

been deliberate. Grave 42 is the richest single Anglo-Saxon grave in the North

East defined by the quantity and quality of the material found. The main

pendant is unique in its shield like shape. The pendant is made of gold with 57

small red gemstones sitting on a thin gold alloy foil. The pendant may have

been made from gold coins from the continent that had been debased.

During the seventh century CE, burial

practises in England had changed. The people had converted to Christianity and

Anglo-Saxon kingdoms had emerged. The more gold or precious objects the more

important the person.

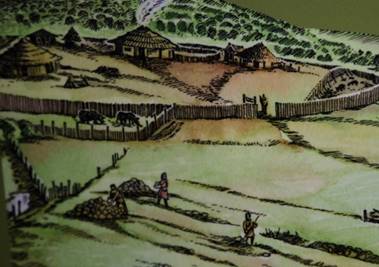

This diorama

at the Kirkleatham

Museum represents the Royal Saxon settlement

excavated at modern day Street House. It shows the unusual layout of the

cemetery, including the bed burial structure, the people and the building of

the settlement, and a small ship at the beach at nearby Skinningrove, as her

crew traded goods with the local inhabitants.

Lindisfarne became one of

the focal Christian centres in Europe between about 650 to 750 CE. It gained

power and wealth, taking grants of land from kings and noblemen, and many

precious objects.

642 CE

Oswald died after a short

reign in 642.The new king was Oswy (Oswald’s brother). He gave land on six

estates to monasteries through Deira including Streoneshalch (later Prestby)

near Whitby in 657.

634 CE

Edwin's successor, Oswald (634 to 642 CE), dominated the northern region from

his royal fortress at Bamburgh. He was sympathetic to the Celtic church and

around 634 he invited Aidan from Iona to found a

monastery at Lindisfarne as a base for converting Northumbria to Celtic

Christianity. The monastery at Lindisfarne observed Irish Christian customs.

Aidan was the first Bishop

of Lindisfarne. He was known as the ‘Apostle of Northumbria’. He died in 651

and was reportedly buried in the church at Lindisfarne.

Aidan soon established a

monastery on the cliffs above Whitby with

Hilda as abbess.

Further monastic sites were established at Hackness and Lastingham and Celtic

Christianity became more influential in Northumbria than the Roman system.

There is a traditional

story that a monastery was built at Oswaldkirk in Ryedale, but was never

finished.

633 CE

Edwin’s defeat at the

Battle of Hatfield Chase by Penda/King Caedwalla of Mercia in 633 was followed

by continuing struggles between Mercia and Northumbria for supremacy over

Deira.

The Northumbrian empire

briefly fell apart, but it was recovered by the Christian King Oswald.

627 CE

Edwin converted to the

Christian religion, along with his nobles and many of his subjects, in 627 and

was baptised at Eoforwic. Edwin built the first church at Eoforwic (York)

amidst the Roman ruins and it was later replaced by a larger stone church.

Stone

crosses or spelhowes/spel crosses started to appear in the landscape,

which seem to have been meeting places of early local government. There is a story that Kirkdale church was first built on

the site of such a stone cross.

617 CE

A later ruler, Edwin of

Northumbria (son of Aelle of Northumbria)(617 to 633)

completed the conquest of the area by his conquest of the kingdom of Elmet,

including Hallamshire and Leeds, in 617 CE. He killed Æthelfrith and became

King of all Northumbria.

Edwin married Princess Aethelburgh

of Kent who brought a priest, Paulinus, from Augustine’s mission in Canterbury

and Edwin was baptised in 627 CE.

604 CE

Æthelfrith took over Deira

in about 604 CE and there was significant expansion of Anglo Saxon power.

From about

604 CE, Æthelfrith was able to unite Deira with the northern kingdom of

Bernicia, forming the kingdom of Northumbria, whose capital was at Eoforwic,

modern day York.

By the early seventh

century, there was a diversity of language – Germanic, Brittonic, Gaelic and

Pictish and later Norse. In the north, predatory chieftains were occupied in

raiding, rustling and slaving. Rival kingdoms appeared with Northumbria emerging

as the most powerful, with its main city at York. (Robert Tombs, The English and their History, 2023,

23).

599 CE

King Aethelric ruled Deira in about 599 to 604 CE.

597 CE

Pope Gregory sent

Augustine, prior of a Roman monastery to Kent on an ambassadorial and religious

mission to convert the Angli, and he was welcomed by King Aethelberht.

The English church would

come to own a quarter of cultivated land in England and it brought back

literacy. English identity began in a religious concept.

580 CE

The historian Procopius

(500 to 565 CE) described the people of Brittia as Angiloi to

Pope Gregory the Great, Gregory had seen fair haired slaves for sale and

replied that they were not Angles, but angels. His pun is sometimes

taken to define the origin of the English and Gregory continued to class them

as a single peoples.

Hence there grew a single and

distinct English church. It adopted Roman practices in its dogma and liturgy

(as later confirmed at the Synod of Whitby in 663 CE), but it venerated English

saints and developed its own character.

569 CE

King

Aella ruled Deira in about 569 to 599 CE.

|

|

|

559/560 to 589 |

Ælla (Aelli) |

|

589/599 to 604 |

Æthelric (Aedilric) |

|

Bernicia Dynasty 593/604? to 616 |

Æthelfrith.

Killed in battle |

|

Deira Dynasty 616 to 12/14 October 632 |

Edwin. Killed in battle by Cadwallon of

Gwynedd and Penda of Mercia |

|

late 633 to summer 634 |

Osric |

|

Bernicia Dynasty 633 to 5 August 642 |

Oswald. Killed by Penda, King of

Mercia; Saint Oswald |

|

642 to 644 |

Oswiu |

|

Deira Dynasty 644 to 651 |

Oswine. Murdered |

|

Bernicia Dynasty summer 651 to late 654 or 655 |

Æthelwold.

Restored |

|

654 to 15 August 670 |

Oswiu |

|

656 to 664 |

Alchfrith |

|

664 to 670 |

Ecgfrith |

|

670 to 679 |

Ælfwine |

560 CE

There is a legendary story

that an Anglian called Soemil founded the Kingdom of Deira. There were early

settlements at Fyling south of Whitby. Early movement inland tended to branch

out along the old Roman roads.

The indigenous population

suffered from mid sixth century plague and rising water levels, so it is

possible that there was little resistance to the Angles.

Circa 500 CE

In the late fifth and

early sixth centuries Angles from the Schleswig-Holstein peninsula began

colonising the Wolds, North Sea and Humber coastal areas.

Fifth Century CE

At the end of Roman rule

in the fifth century, the north of Britain may have come under the rule of

Romano-British Coel Hen, the last of the Roman-style Duces Brittanniarum (Dukes

of the Britons). However, the Romano-British kingdom

rapidly broke up into smaller kingdoms and York became the capital of the

British kingdom of Ebrauc. Most of what became Yorkshire

fell under the rule of the kingdom of Ebrauc but Yorkshire also included

territory in the kingdoms of Elmet and an unnamed region ruled by Dunod Fawr,

which formed at around this time as did Craven.

Saxon settlements appeared across Britain, especially to the south and east,

but also in the north. The Saxons didn’t displace the indigenous population,

but there was violence evidenced by hoards of treasure buried to escape the

increasing threat.

The population of Britain

fell from a few million to fewer than one million people after the Romans left

in the fifth century. Over the next few centuries, groups of Angles and Saxons

arrived from northwest Germany and southern Denmark, taking advantage of a

‘failed state’. They established a dominant Anglo-Saxon culture which

influenced the lands that would become England.

Life was nasty, brutish

and short. This was the context of the Arthurian legends.

Genetic mapping indicates that

most of the eastern, central and southern parts of England formed a single

genetic group with between 10 and 40 per cent Anglo-Saxon ancestry. However,

people in this cluster also retained DNA from earlier settlers. The invaders

did not wipe out the existing population; instead, they seem to have integrated

with them.

Transforming events were

taking place across the world at this time – the Chinese Empire reunited under

the Tang dynasty, the Roamn empire reestablished itself at Constantinople and

Islam began its conquest of western Asia and Iberia (Robert

Tombs, The English and their History, 2023, 21).

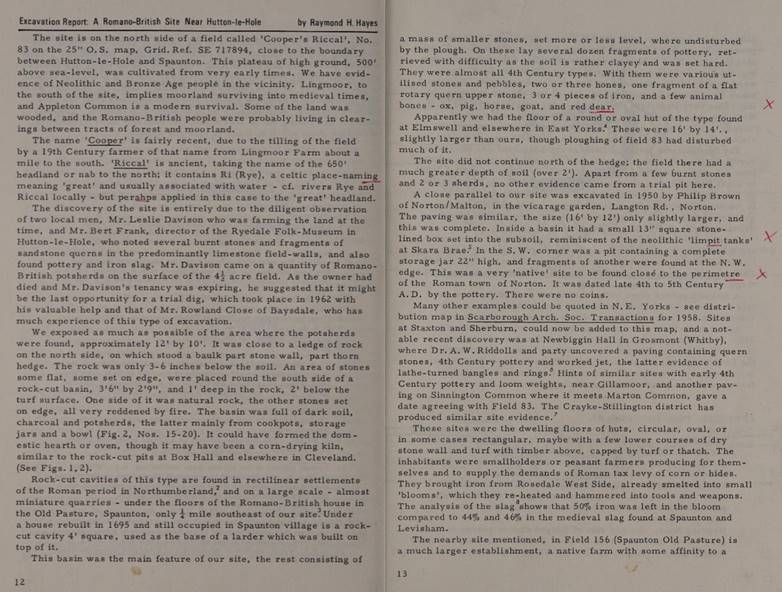

The Roman Period

(410 CE back to 71 CE)

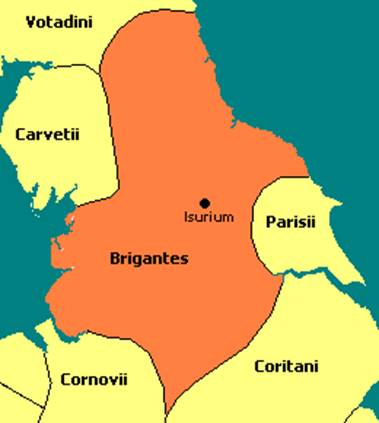

Yorkshire

was part of the Roman Empire between 71 CE and 410 CE. The Romans did not

advance into north eastern Yorkshire beyond the River Don, which was the

southern boundary of the Brigantian territory.

The legions were recruited

from all across the Roman Empire. However, there is very little evidence today

of a genetic legacy from other Roman dominions.

The Romans built roads

northwards to Eboracum (modern York), Derventio (Malton) and Isurium Brigantum

(Aldborough).

During the period 700 BCE

to 410 CE, the climate was cooler and wetter. Soils on the high ground of the

North Yorkshire moors had been exhausted. Farmers moved to lower ground. The

moorland generally reached about the same extent as exists today.

410 CE

There is an In Our Time podcast on the causes and events leading to the fall of the Roman Empire

in the 5th century and assesses the role of Christianity, the Ostrogoths,

the Visigoths and the Vandals.

408 CE

Roman Britain faced

threats from north Britain and Scots in Hibernia. Saxons from northern Germans

and southern Scandinavia started to threaten the north sea coast and the Romans

stationed increasing troops along the coast and built extensive fortifications.

By the time of a significant Saxon attack in 408 CE, Britain was becoming a

drain on Roman resource who were facing simultaneous threats across Europe.

402 CE

In 402 CE the Roman garrison at Eboracum was

recalled because of military threats from other parts of the empire. The

Roman legions started a process of withdrawal from Britain.

306 CE

Constantius

I died in 306 CE during his stay in Eboracum, and his son Constantine the Great was

proclaimed Emperor by the troops based in the fortress.

296 CE

A century or so of

relative peace seems to have ended by about 296 CE and Eboracum became

more of a command post for the Dux Britanniarum, the Roman Commander of

northern Britain. The Dux Britanniarum was a military post in Roman Britain,

probably created by Emperor Diocletian or Constantine I during the late third

or early fourth century. The Dux (literally, "(military) leader" was

a senior officer in the late Roman army. His responsibilities covered the area

along Hadrian's Wall, including the surrounding areas to the Humber estuary in

the southeast of today's Yorkshire, Cumbria and Northumberland to the mountains

of the Southern Pennines. The headquarters were in the city of Eboracum

(York). The purpose of this buffer zone was to preserve the economically

important and prosperous southeast of the island from attacks by the Picts

(tribes of what are now the Scottish lowlands) and against the Scots (Irish

raiders).

There is an In Our Time podcast on the Picts.

The fortifications at

Malton were rebuilt.

207 CE

During his stay 207–211

CE, the Emperor Severus proclaimed Eboracum capital of the province of Britannia

Inferior, and it is likely that it was he who granted York the privileges of a

'colonia' or city.

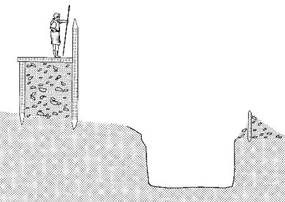

122 CE

The Emperor Hadrianus

sealed off the far north by a military zone focused on Hadrian’s Wall which was

built between 122 to 138 CE and was one of the most significant engineering

projects of the ancient worlds.

During the Roman period,

Most of Britannia remained rural: 80 per cent of the population lived in over

100,000 small settlements and some 2,000 villas (Robert

Tombs, The English and their History, 2023, 12).

77 CE

In 77 CE Agricola became

governor and extended Roman domination northwards.

The rulers organised agriculture

and economic activity, some based on slave labour, around villas in the

countryside. They expanded towns and built roads to speed the progress of their

legions between military forts. Yet in the more remote areas of western and

northern Britain, life continued much as before.

The Romans came into the

area further east to patrol the coast. They built roads, part of which still

exist and warning stations on the cliffs at places like Huntcliffe. It is

possible that Roman patrols may have passed through the heavily forested dales

flowing from the high moors, including Farndale, but there is no

evidence that they stopped there, and it seems more likely that they would have

ignored the impenetrable woodland areas.

There is an In Our Time podcast on Roman Britain.

71 CE

A significant military camp was founded by the Romans as Eboracum

(modern day York) in 71 CE.

Urban settlements grew around the Roman fortifications at York (Eboracum),

Malton and Stamford. Eboracum became a significant Roman provincial capital.

To the south Roman urban settlements grew around fortifications

at Calcaria (Tadcaster) and Danum (Doncaster).

The Roman legions brought

with them craftsmen who made nails, shoes and pottery, or maintained iron edged

tools, lead piping and the like. The towns around the military zones developed

their own craftsmen and patterns of trade. The Roman army needed food, clothes,

horses, drink and the like. The towns developed forms of amusement and

relaxation and amenity and administration.

Evidence of imported goods

from the Roman period have been found, Bronze statues of Venus and Hercules

have been found around Malton. Pieces of toilet seats have been found in

Gillamoor.

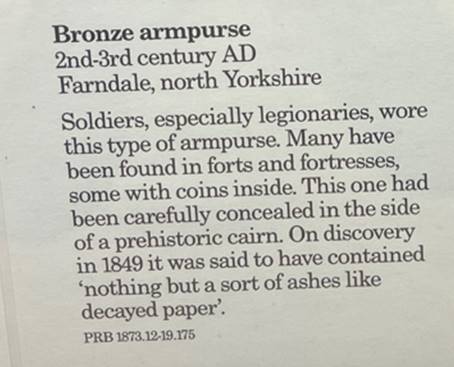

There has been a find of a bronze arm-purse on a high moor track

above Farndale in 1849.

Roman copper-alloy arm-purses appear to have been principally, if not

exclusively, a male, military accoutrement, with examples found both in

auxiliary and legionary contexts in Britain and on the Continent. British

examples include finds from Birdoswald (x2), Corbridge, South Shields,

Thorngrafton (near Housesteads), Colchester, Wroxeter, Silchester and Farndale.

The

find is from a track above Farndale, so may not evidence Roman

activity within the dale, but it does suggest some influence, perhaps

patrolling, in the immediate vicinity.

At the time

of writing, the purse can be seen in the British Museum (Museum Reference Number

1873,1219.175), on display in Room 49, case 9. This gallery is located on the

upper floor of the museum.

43 CE

From the year 43 CE, Roman

influence had transformed the way of life of people in southern and eastern

Britain. The emperor Claudius commanded a force of some 40,000 men, with

elephants to boot. They were grouped into four legions supported by auxiliaries.

Over the following decades

the Romans came to dominate Britain. Resistance by Caratacus was quickly

subdued and the druids were massacred on Anglesey in 60 CE. He then faced

revolt to the east from the Iceni and their king’s widow, Boadicea.

There is an In Our Time podcast on the Druids.

There

is an In Our Time podcast on Boudica.

55 and 54 BCE

Prior to the Roman period

in Britain, Julius Caesar, having expanded northwards and fighting his wars in

Gaul, was drawn to an early invasion when Britons allied with the Gauls. He

landed in Kent with a force about 30,000 strong and advanced to the Thames.

Though he met a disunited resistance, he withdrew quickly to deal with the

ongoing threat to the Roman army in Gaul.

The Iron Age (70 CE

back to 700 BCE)

The

Bronze Age people, such as the Beaker Folk were conquered by Celtic speaking

invaders from the Mediterranean and later focused in northern Gaul. They

settled in Britain and became known as the Brigantes, who have colloquially been referred to

as Ancient Britons. The Celts were skilled horsemen. They went into battle with

iron wheeled, horse drawn chariots, and attacked their enemy with swords and

spears.

There is an In Our Time podcast on the dawn of the European Iron Age, a period of

great upheaval when technology and societies were changed forever.

The Brigantes were not the only Celtic tribe to

occupy northeast Yorkshire. In Holderness and the Wolds area, were a folk known

as the Parisii (who came from France and Belgium).

The

Brigantes were a highly organised society, with a hierarchy of military rulers.

The mobility provided from their horsemanship enables them to control lager

areas.

Their

farmsteads were made up of groups of small square or rectangular fields and

were often enclosed by low walls of gravel or stones. Their huts were made of

branches, or wattle and stood on low foundations of stone.

There was a massive hill fort at Roulston Scar, which dates back

to around 400 CE. The site covers 60 acres, defended by a perimeter 1.3 miles

long. It is the largest Iron Age fort of its kind in the north of England.

There are

outlines of other such settlements near Grassington and Malham. The most

impressive Iron Age remains are at Stanwick, north of Richmond.

The Brigantes fought hard to defend themselves against the Roman invaders.

Several large fortifications witness their efforts. The last inhabitants of the

area before the Romans were illiterate, but left their mark in the place names

of Yorkshire. Many Yorkshire rivers carry Celtic

names - Aire, Calder, Don, Nidd, Wharfe.

The Brigantes were a Celtic

tribe who lived between the Tyne and the Humber.

The Brigantes and Parisii

were led by a tribal leader, sometimes elected, and sometimes from a leading

aristocratic family such as Boudicca who later fought the Roman army. They

lived in large settlements, sometimes on hilltops and sometimes in the lowlands.

There is such a site at Stanwick near Darlington where pottery has found

covering a large area which had come from the continent. The main Parisii

settlement was probably close to Brough near Hull. There is evidence that the

aristocracy lived in rectangular enclosures often about 60 by 80 metres with

two metre wide defensive ditches piled high inside for further protection. The

homes, similar to Iron Age roundhouses, may have been established in groups of

two or three. Each enclosure farm worked about 250 acres and the fields around

the farms grew cereals and hay for winter feed. The non aristocratic folk would

have worked the land in the enclosure farms for their masters.

The Brigantes and Parisii

have left evidence across modern Ryedale of round houses within enclosed sites.

Roulston Scar at Sutton Bank is a limestone

cliff which overlooks the Vale of York, between Helmsley and Thirsk (some 20km

to the west of Kirkbymoorside and Farndale). It is a large Iron Age promontory

fort dating to about 500 to 400 BCE.

Iron furnace remains and

slag from smelting have been found. Iron ore may have been mined in Rosedale. Those

living closer to the sea may have picked up or from the beaches. The Bronze Age

is the period when for the first time the land had been cleared for growing

crops and rearing cattle and sheep. Significant advancement was made in culture

and politics and the use of land. The landscape may have looked similar to the

present day but with more woodland in the valleys and no towns or roads. There

may have been tracks for wheeled vehicles.

Costa Beck is a small river in Ryedale, North Yorkshire. Excavations from

ther 1920s have revealed Iron Age lakeside settlements through the Vale of Pickering.

Animal bones, pottery sherds and a human skull have been excavated.

There are

several sites in the Pickering Vale, including at Heslerton where there were

small enclosures for stock breeding and growing crops in the wetlands around

the once Lake Pickering.

In 320 BCE, the Greek

explorer, Pytheas sailed around Britain and called it Pretannike,

probably from the Celtic for ‘tatooed’, from which evolved Britannia

over time. The larger island of the British Isles came to be called Alba

or Albion and the western island (modern Irland) Ivernia or Hibernia.

Centuries later in the History of the Kings of

Britain by Geoffrey of Monmouth,

in 1136, a story emerged that the Trojan Brutus had landed in Albion finding

only giants and named the land Brutaigne.

The Bronze Age (700

BCE back to 1,800 BCE)

The use of

bronze was probably introduced into Yorkshire by the Beaker Folk, who arrived in the area via the Humber

Estuary in about 1800 BCE.

Beaker folk

They came across the Wolds and crossed

the Pennines. Their name is derived from their tradition to bury beaker shaped

urns with their dead.

Beaker Folk reached Malham Moor and occupied sites on the Wolds. There is

evidence that they cultivated wheat and there is evidence of trade. They

imported flat bronze axes from Ireland. They exported ornaments made of Whitby jet. They traded in salt and had sea

connections with Scandinavia.

Possibly transition into the Bronze Age

came about by invasion, or it may have evolved through trade and peaceful

contacts.

The people of the Bronze Age continued

to hunt in upland areas. There have been finds of their barbed and tanged flint

arrowheads. Gradually these were replaced with metal tools and weapons. There

is evidence during the Bronze Age of metal working and tin mining, leather and

cloth manufacturer, pottery and salt production. There was domestic trade and

trade beyond the island’s shores.

The population steadily grew to perhaps

about 2 million.

The Bronze age was a time of changes in

burial rituals. Bodies were buried beneath circular mounds (round barrows)

often accompanied by bronze artefacts. There are

many barrows in upland locations on the Wolds and the Moors.

Early Bronze Age burials were performed

at Ferrybridge Henge.

There is a Street

House Long Barrow (later added to by an Anglo Saxon

royal burial site) at Loftus, where many

later Farndales lived and are buried.

Round barrows of the early

part of the Bronze Age are the most conspicuous archaeological features of the

North York Moors. The

scarcity on lower ground is due mainly to agricultural activity. Those on

higher ground have generally been found to contain cremations, while those on

lower ground in limestone areas contained both burnt and unburnt bodies. The

skeletons are most often accompanied by pottery (beakers, food vessels,

collared urns and accessory cups), and flints, and sometimes by jet ornaments,

stone battle axes and occasionally by bronze daggers. Collared urns and

cremations have also been found with stone embanked circles such as at Great Ayton moor.

Yorkshire

Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 22 January 1936: In Cleveland, and especially on the eastern moorlands,

remains are few and far between. Yet Guisborough has produced a bronze helmet,

and Farndale moor a bronze arm purse, probably loot; while on the coast from

Saltburn to Filey stand the foundations of five watchtowers erected at the time

of Saxon peril.

The Ryedale

Windy Pits are archaeologically significant natural underground features

within the North York Moors National Park. This series of fissures in

the Hambleton hills, near Helmsley, is located on the western slope above the

river Rye. Warm or cold air rises from the fissures and comes into contact with

the air outside the entrance. In winter a steamy vapour rises in puffs or jets

from the holes. There are over 40 known windy pits, but only four windy pits

have known significant archaeological deposits. These are Antofts, Ashberry,

Bucklands and Slip Gill. The windy pits have strange vertical shafts with

occasional horizontal chambers rising within the limestone cliffs. They are

accessed from the surface through small openings in the woodland floor. The

near vertical shafts are sometimes 70 feet deep. In all the skulls and bones of

at least eight people were found in Antofts and animal bones from pigs, wild

boar, red deer, roe deer, sheep, goat and dog as well as four or five beakers

have also been found. The human remains include the skull of an elderly woman

with a fatal wound inflicted by a long sharp, metal weapon and many

disarticulated human bones.

Bronze age

hoards of axes cast in bronze have been found at Keldholme and Gillamoor. There

are barrows and tumuli such as at Whinny Hill Farm near Kirkbymoorside and

Keldholme and a road in the centre of Kirkbymoorside, Howe End, circles the

site of a howe, a large round mound which contained several burial sites.

There is an In Our Time podcast on the Bronze Age collapse, sudden,

chaotic change around 1200 BC, mainly in the eastern Mediterranean.

The Neolithic

Period, the New Stone Age (3,000 BCE to 1,800 BCE)

The New Stone Age was the

period when tool making skills produced stone axes, flint axes, arrow heads,

spear points, fired clay beakers and woven cloth.

A revolutionary advance

was made in the cultural development of northeast Yorkshire at around 3000 BCE.

This was the arrival from continental Europe of the first Neolithic (New Stone

Age) settlers. These people must have crossed in boats; probably in dug out

canoes. The Neolithic Revolution involved arable farming and the domestication

of animals.

Neolithic society made pottery, weaved cloth and

made baskets. These people no longer lived a semi nomadic existence. Permanent

settlements were built, like to one at Ulrome,

between Hornsea and Bridlington, where a dwelling built on wooden piles

on the shore of a shallow lake has been found.

Ulrome

The Neolithic people buried their dead with ceremony, in chambered mounds called barrows. There are examples of long and round barrows.

The

start of stone age farming in the area of the north Yorkshire moors was in

about 3,000 BCE, though there is some evidence of

farming from about 5,000 years ago. By 3,000 BCE permanent settlements were

built by Neolithic people.

From about 2,000 BC huge prehistoric

monuments appeared in the Megalithic Period. The organisation required erect the

large megalithic structures and the barrows suggests highly developed society.

The largest standing stone in Britain is

a single pillar of grindstone, 25 feet high. It dominates the churchyard at Rudstone, a few miles west of

Bridlington. The nearest source of stone is 10 miles north of the site.

Small village communities

became settled, more reliant upon domestic animals and less on hunting. They

built stone enclosures for animals, and developed rituals for the dead and

forms of religion. Burial was in long barrows, in caves and in stone lined graves.

The development of grinding

and polishing stone allowed a variety of stone as well as flint to be used.

Hard boulders from local glacial deposits were useful raw material. Flint axes, some polished, were found at Peak, South of

Robin Hood’s Bay and green stone axes were found in Seamer. Seven miles east of

Pickering in the centre of a round barrow were found a burnt flint knife and a

round axe.

The Yearsley Moor long barrow has been excavated at

the home of the later ancestors of the Ampleforth line of

Farndales.

The Mesolithic

Period (3,000 BCE back to 9,500 BCE)

3,000 BCE

Over the past half millennium, the landscape of Britain had been

transformed and by 3,000 BCE ritual sites spread southwards from the inlands

far to the north.

4,000 BCE

The earliest evidence of

domestic crops and animals in the region dates back to about 4,000 BC. Permanent settlements were built by the

Neolithic people and their culture involved ceremonial burials of their dead in

barrows. The development of farming in the Vale of Pickering during the

Neolithic period is evident in the distribution of earth long

barrows throughout the area. These early farmers were the first to destroy

the forest cover of the North York Moors. Their settlements were concentrated

in the fertile parts of the limestone belt and these areas have been

continuously farmed ever since. The Neolithic farmers of the moors grew crops,

kept animals, made pottery and were highly skilled at making stone implements.

They buried their dead in the characteristic long low burial mounds on the

moors.

We discover the first hints of our distant ancestors who would

beget their poacher

descendants and the inspiration for Robin Hood.

Their food came from wild animals, birds and fish and from berries

and other fruit. They sheltered in caves, such as Kirkland Cave near Pickering.

There is evidence in such caves of animals which had previously flourished in a

warmer sub-tropical climate such as the bones of lions, elephants, rhinoceros

and hippopotami. The Leeds Hippopotamus was found in a clay pit at Wortley in

1854. However when the first humans arrived, the climate was still sub-arctic

and the earlier animals which were found were mammoths, woolly rhinoceros and

reindeer.

5,000 BCE

In a different area of Britain,

the Severn Estuary footprints date back to about 5,000 BC. On the southern edge of the Vale of

Pickering lies West Heslerton, where recent excavation has revealed

continuous habitation since the Late Mesolithic Age, about 5,000 BC. This

site has revealed a great deal of dwelling and occupation evidence from

the Neolithic period to the present day.

6,500 BCE

As the climate continued

to warm, sea levels rose, and Britain became an island. By about 6,500 BC, the British Isles became an island. By 5,000 BC Britain was separated

from mainland Europe after rising sea levels had created the southern area of

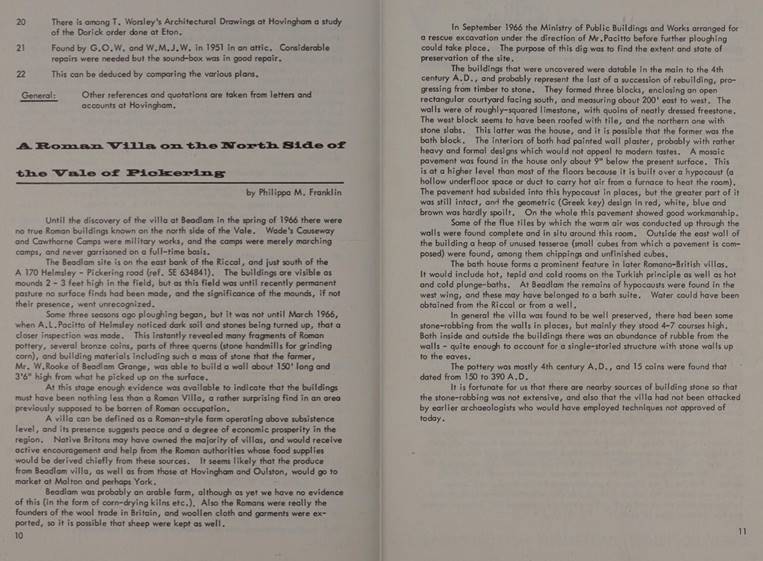

the North Sea. Chapel Cave, near Malham in the northern Pennines, may