|

|

York

Historical and geographical information

|

|

Dates

are in red.

Hyperlinks

to other pages are in dark

blue.

Headlines

are in brown.

References

and citations are in turquoise.

Contextual

history is in purple.

This webpage about the York has the following section headings:

- Farndale

family history and York

- York, overview

- Timeline of York history

- Links, texts

and books

The Farndales of York

The

York 1 Line were the descendants of

Johannis de Farndale (FAR00030), a saddler,

made Freeman of York in 1363. His son was Johannis de Farendale

(FAR0035),

freeman of York. John Fernedill (FAR0048A)

The

York Southcliffe Line

were the descendants of Alice Farndale (FAR00058).

Others

were Wylson, wyff of Farndayll

(FAR00065);

William Farndale (FAR00220A),

York (Bishop Wilton); Elias Farndale (FAR00224), York (Bishop

Wilton); William Farndale (FAR00281), York

(Bishop Wilton); Joseph Farndale (FAR00285);

Thomas Farndale (FAR00317);

John Farndale (FAR00324),

York (Bishop Wilton); John Farndale (FAR00365); Jane

Ann Farndale (FAR00371);

William Brown Farndale (FAR00384);

Mary Farndale (FAR00393);

Joseph Farndale (FAR00401);

Hannah Farndale (FAR00407);

Jane Farndale (FAR00422);

William Farndale (FAR00425);

William Farndale (FAR00435);

George Farndale (FAR00437);

Henry Farndale (FAR00446);

Mary Farndale (FAR00461);

Joseph Farndale (FAR00463);

Elizabeth Farndale (FAR00470);

Sarah Farndale (FAR00513);

Louisa Farndale (FAR00518);

Mary Emily Farndale (FAR00529);

William Edward Farndale (FAR00576);

Joseph Farndale (FAR00593);

Ellen Farndale (FAR00612);

Lily Farndale (FAR00635);

William Henry Farndale (FAR00655);

John William Farndale (FAR00663);

Florence Farndale (FAR00671);

Arthur Farndale (FAR00694);

Arthur E Farndale (FAR00706);

Ella Farndale (FAR00727);

Lily D Farndale (FAR00768);

John Farndale (FAR00805);

Lorna Farndale (FAR00927);

Denise A Farndale (FAR00949);

Lillian P Farndale (FAR00956);

John Leslie Farndale (FAR00979);

Lydia A Farndale (FAR00991);

John Anthony Farndale (FAR01021).

Joseph Farndale CBE KPM (FAR00463) became

Chief Constable of Margate, York and later of Bradford. He was Chief Constable

of York Police from 1897 to 1900.

York

York is a city in North Yorkshire,

located at the confluence of the Rivers Ouse and Foss. It is

the county town of the historic county of Yorkshire.

York Timeline

For thousands of years before the Romans came to the

area, prehistoric folk hunted, farmed and lived in communities. They discovered

how to exploit stone, then bronze and later iron. The first metal objects were

made from copper, but by adding tin, they became much stronger.

Flint tools, the Yorkshire Museum

Pottery vessels for cremated remains

43 CE

The area of York was inhabited by a Celtic tribal

confederation, the Brigantes.

The Romans came to Britain, to stay, from 43 CE.

Initially the Romans didn’t venture north of the Humber and Don, but traded

with the Parisii, though the Brigantes

remained hostile.

Cartimandua was the Brigantes’

queen. Her position was threatened by an open revolt by her husband, Venutius. It may have been this revolt that provided a

purpose for Roman intervention.

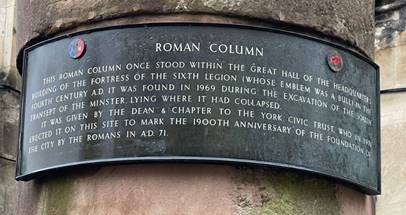

Eboracum

71 CE

In 71 CE the new Roman Governor, Quintius Petillius Ceralius marched north

from Lincoln to occupy Brigantes and Parisii territory. The Ninth Legion erected a large camp

near where Malton (northeast of York) stands today.

Legionary Tile, 70 to 120 CE (Yorkshire Museum)

They found that the area of York was an ideal site for

a fort in a potentially neutral zone between the Brigantes

and the Parisii.

A larger military camp was constructed by the Romans

as Eboracum (modern day York) in 71 CE. The Romans built an earth-and-timber

fort on the north-east side of the Ouse, which formed the basis for York’s city

centre today. As this fortress grew in importance, a civilian settlement

developed on the opposite bank of the river.

Soldiers stationed in Eboracum came from across

Northern Europe, only a few could have come from Italy. The Ninth and the later

Sixth Legion had been stationed in Spain, Africa, Germany

and Pannonia before they came to Britain.

Urban settlements grew around the Roman fortifications

at Eboracum, Malton and Stamford. Eboracum became the Roman provincial capital.

The remains of the Roman Basilica can be seen in the undercroft of York Minster, and the remains of a bathhouse

in the cellar of the Roman Bath pub.

Roman coinage (The Yorkshire Museum)

The city was therefore founded by

the Romans as Eboracum in 71 CE. The civilian

settlement was just across a bridge, or reached by

ferry. Soldiers from the fortress could relax there and soldiers and officers

sometimes lived in residential properties or large private houses alongside the

civilian population.

The heart of the Roman fortress was the principia, the

Headquarters.

Roman troops were garrisoned at York for more than 300

years but little is known of the history of the city

during that period, partly because systematic and extensive excavation is

impossible and partly because the city is so infrequently mentioned in early

writings. Two events, however, were of sufficient importance in the history of

the empire to earn a mention by Roman writers. Between 208 and 211 the Emperor Severus was at York while he was conducting

campaigns against the Caledonians and in the latter year he died there.

Accounts of his death make some obscure references to York's topography and

mention a temple of Bellona and a domus palatina. It

was from York, moreover, that Severus dated a rescript of 5 May 210 headed Eboraci. Almost a century later, in 305, Constantius

Chlorus died in the city and Constantine was acclaimed there as his successor.

Both Severus and Constantius Chlorus were using York as a base for military expeditions and it was as the strategic centre of Roman

Britain that the fortress was most important. (A History of the County of York: the

City of York. Originally published by Victoria County History, London, 1961).

120 CE

In about 120 CE, the Ninth Legion was replaced there

by the Sixth Legion, and both the fort and the civilian settlement were rebuilt

in stone.

122 CE

Emperor Hadrian (of Spanish origin) visited the

settlement during his journey to build his border wall. Men from York’s Sixth

Legion built Hadrian’s Wall.

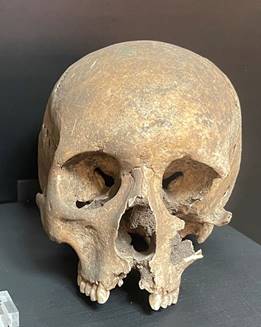

Skull of a man in his fifties buried between York and Calcaria (Tadcaster) (Yorkshire Museum). Skeleton of a wealthy lady found

close to the River Ouse, found accompanied by unusual

and expensive objects (Yorkshire Museum).

The cult God Mythras

207 CE

During his stay 207–211 CE, the Emperor Severus

proclaimed York capital of the province of Britannia Inferior, and it is likely

that it was he who granted York the privileges of a 'colonia' or city.

Emperor Septimius Severus (of Libyan origin), who was

leading campaigns against the Caledonians to the north, arrived in York with a

very large retinue of civil servants and soldiers, including the Praetorian

Guard. He also brought his wife, Julia Domna, and their sons Caracalla and

Geta. Severus died in York in February AD 211 and, after a bloody succession

squabble in Rome, Caracalla became emperor.

At this time, Eboracum was designated the capital of

Britannia Inferior, the province of northern Britain, and gained the highest status

that a city could have in the Roman empire, becoming a colonia.

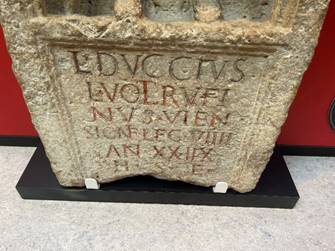

Sandstone statute of Mars 300 to 400 CE (Nunnery Lane,

York, now at The Yorkshire Museum) Lucius Duccius

Rufinus, a 28 year old standard bearer from Viennes,

France (Mickelgate, York, now the Yorkshire Museum)

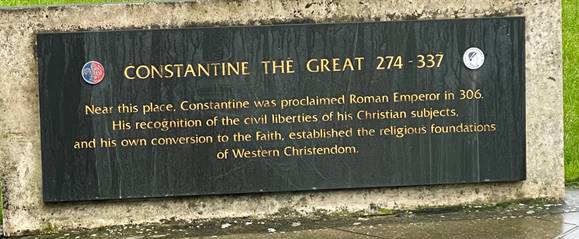

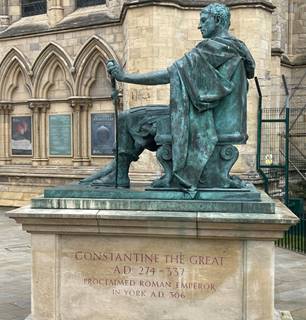

306 CE

Constantius

I died in 306 CE during his stay in York, and his son Constantine the Great was

proclaimed Emperor by the troops based in the fortress.

Constantius Chlorus (of Serbian origin) became the

second emperor to die in York on 25 July 306 CE. He had visited Britain several

times during his lifetime. He was accompanied at the time by his son,

Constantine, who eventually succeeded him. Constantine would have a profound

impact on the city and on global politics.

Constantius and Constantine (Yorkshire Museum)

The veteran soldier Caereslus

Augustinus had lost his wife. Flavia Augustina and his two children. This stone

carving (119 to 410 CE) seems to depict his idea of how they might have grown

up as a family, had they lived. (Yorkshire Museum)

Tombstone (200 to 300 CE) of Julia Velva. Her heir

Aurelius Mercurialis would gather at the tomb on the

anniversary of her death and would have believed she could take part.

(Yorkshire Museum).

313 CE

Constantine supported Christianity, and in 313 CE

issued an edict of religious tolerance.

314 CE

Eboracum had its first bishop, Eborius,

appointed.

In 314 CE a bishop from York attended the Council at

Arles to represent Christians from the province.

400 CE

While the Roman colonia and fortress were on high

ground, by 400 CE the town was victim to occasional flooding from the Rivers

Ouse and Foss, and the population reduced.

Fifth century

York declined in the post-Roman era,

and was taken and settled by the Angles in the 5th century. The

population shrank, trade declined, and buildings were abandoned.

Apart from … slight indications that the Germanic

invasions may not at first have been inimical to York, nothing is known of the

fate of the city in the 5th and 6th centuries. By the first decade of the 7th

century, and perhaps earlier, it lay within but not at the heart of the English

kingdom of Deira. (A

History of the County of York: the City of York.

Originally published by Victoria County History, London, 1961).

However

cemeteries dating from this period show that Anglo-Saxons settled in the area

as early as the fifth century.

Eoforwic

Seventh century

From about 600 CE, York became

capital of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Deira. Its Anglo-Saxon name, Eoforwic, suggests that it was an important commercial

centre; all ‘-wic’ towns in the period being

important trading emporia. By the early seventh century, it was also a royal

base for the Northumbrian kings.

Reclamation of parts of the

town was initiated in the 7th century under King Edwin of Northumbria, and York

became his chief city. It was the capital of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Deira

and later the combined centre of Northumberland with the merging of Deira with

Bernicia. Its Anglo-Saxon name, Eoforwic, suggests

that it was an important commercial centre as the wic

towns were important trading centres. By the early seventh century, it was also

a royal base for the Northumbrian kings.

601 CE

When in 601 Gregory the Great sent the pallium to

Augustine he planned to divide Britain into two sees, one of which was to have

its centre at York. When the time was ripe the Bishop of York, like Augustine

in the southern province centred on London, was to ordain twelve bishops and

enjoy the rank of metropolitan. This apparently sudden reappearance of York in

the role of an internationally recognized metropolis has doubtless some

connexion with the facts of population and economics. The Roman roads alone would

have sufficed by this date to focus Northumbrian communications and commerce in

such a degree as to re-create at York the largest urban settlement in the

north. But these can scarcely have been the only reasons for the choice of

York. Gregory is unlikely to have been ignorant of the traditions of the city

deriving from its status in Roman times and, in particular,

he may have been reminded by his advisers that the city had been the

centre of a bishopric in the 4th century. Though many years were to elapse

before his plan took effect, we may regard the northern metropolitan see as the

most permanent legacy of Eboracum and so, like the papacy itself, a 'ghost of

empire'. (A History of the County of York: the City of York.

Originally published by Victoria County History, London, 1961).

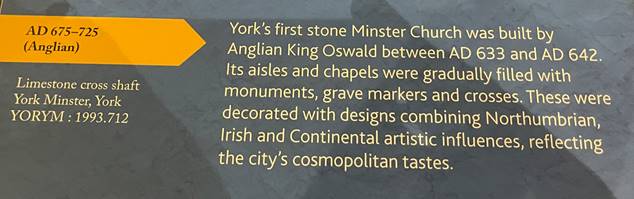

627 CE

After the Roman mission to re-establish Christianity

in Britain, Bishop Paulinus established his church in the city The first wooden

minster church was built in York. It was here that King Edwin was baptised in

627, according to the Venerable Bede.

So King Edwin, with all the nobles of his race and a

vast number of the common people, received the faith and regeneration by holy

baptism in the eleventh year of his reign, that is in the year of our Lord 627

and about 180 years after the coming of the English to Britain, He was baptised

at York on Easter Day, 12 April, in the church of St Peter the Apostle, which

he had hastily built from wood while he was a catechumen and under instruction

before he received baptism. He established an episcopal see for Paulinus, his

instructor and bishop, in the same city. (The Ecclesiastical History, Bede)

Edwin ordered the small wooden church be rebuilt in

stone; however, he was killed in 633, and the task of completing the stone

minster fell to his successor Oswald.

Eighth century

In the following century, Alcuin of York came to the

cathedral school of York. He had a long career as a teacher and scholar, first

at the school at York now known as St Peter's School, founded in 627 AD, and later as Charlemagne's leading advisor on

ecclesiastical and educational affairs.

793 CE

The earliest recorded Viking raid in Britain was the

attack on Lindisfarne in AD 793. At the time the Scandinavian raiders generally

picked largely undefended, wealthy targets such remote monasteries. The

Vikings quickly learned that ecclesiastical centres were good targets.

865 CE

The Viking Great Army first landed in East Anglia on

the east coast of England in 865 CE, but soon turned northwards.

866 CE

In 866 CE, Northumbria was in the

midst of internecine struggles when the Vikings raided and captured

York. As a thriving Anglo-Saxon metropolis and prosperous economic hub, York

was a clear target for the Vikings. Led by Ivar the Boneless and Halfdan,

Scandinavian forces attacked the town on All Saints' Day. Launching the assault

on a holy day proved an effective tactical move, most of York's leaders were in

the cathedral, leaving the town vulnerable to attack and unprepared for battle.

It is possible that its gates were open to let in people from the surrounding

countryside.

Jórvik

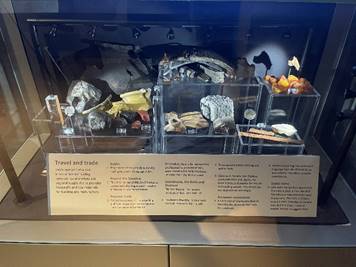

By the end of the ninth century, the Norsemen had established

themselves in York. And so Saxon Eoforwic became Jórvik.

It became the capital of Viking territory in Britain,

and at its peak boasted more than 10,000 inhabitants. This was a population

second only to London within Great Britain. Jorvik proved an important economic

and trade centre for the Vikings. The city was well connected through river

traffic along the Ouse, which linked via the North Sea to the Viking trade

networks that spanned much of the known world at that time. Artefacts from as

far away as Afghanistan have been found in York. There’s

also evidence from the Coppergate site of industrial

production: woodworking, crafting with copper, iron, silver, gold, even

glassmaking – and the raw materials came from far afield. Some were brought

across the Pennines; there was tin from Cornwall, and bones and antlers for

combs and pins from Greenland and Iceland.

Jorvik Museum (Photographs RMF)

Norse coinage was created at the Jorvik mint, while

archaeologists have found evidence of a variety of craft workshops around the

town's central Coppergate area. These demonstrate

that textile production, metalwork, carving, glasswork

and jewellery-making were all practised in Jorvik. Materials from as far afield

as the Persian Gulf have also been discovered, suggesting that the town was

part of an international trading network. Under Viking rule the city became a

major river port, part of the extensive Viking trading routes throughout

northern Europe.

926 CE

By AD 926, the Scandinavian kingdom of York was

brought under the overlordship of King Æthelstan. But

for the next few decades, it was fought over between the Anglo-Saxon kings and

the Viking kings of the Irish Uí Ímair dynasty.

954 CE

The last ruler of an independent Jórvík,

Eric Bloodaxe, was driven from the city in 954 CE by

King Eadred in his successful attempt to complete the unification of England.

York

was absorbed into the English kingdom – but it retained its Anglo-Scandinavian

culture and character. There are records of landholders with hybrid names, and

inscriptions around Yorkshire that are partly in Latin and partly in Old Norse.

1066

In 1066 the Danes, led by the Norwegian King Harold

Hardrada, sailed up the Ouse, with support from Tostig Godwinson and after the

Battle of Fulford, they seized York. King Harold of England then marched his

army north to York in four days to take the invaders by surprise. Live. Bridge.

The rebels were defeated at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in which Harold

Hardrada and Tostig were killed. So far so good. The trouble of course was that

Harold then had to march his exhausted army south again, to confront the second

threat from William of Normandy, near Hastings, and in that episode, he didn’t

do so well.

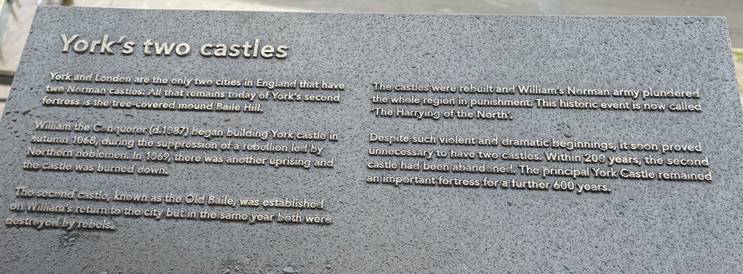

1068

In 1068, two years after the Norman conquest of

England, the people of York rebelled. Initially they were successful, but upon

the arrival of William the Conqueror the rebellion was put down.

William at once built a wooden motte and bailey fortresses at the site of Clifford’s

Tower.

1069

In 1069, after another rebellion, the king built

another timbered castle across the River Ouse. The original

wooden castles were destroyed in 1069 by another rebellion supported by the

Danish King Sweyn II Estridsson.

The Norman response was to set fires that destroyed

swathes of York, including the Minster. William bribed the Danes to leave, then

stamped out local rebellion during the Harrying of the North. and rebuilt the City and the two castles as well as. The remains of the rebuilt castles, now in

stone, are visible on either side of the River Ouse.

York

1080

The first stone minster church was badly damaged by

fire in the uprising, and the Normans built a minster on a new site (parts of

which can be seen in the modern undercroft). Around

the year 1080, Archbishop Thomas started building the first Norman

Cathedral that in time became the current Minster.

1088

Religious communities were established, including the

hugely wealthy Benedictine monastery St Mary’s Abbey, the ruins of which are in

Museum Gardens. The original church on the site was

founded in 1055 and dedicated to Saint Olaf. After the Norman Conquest the

church came into the possession of the Anglo-Breton magnate Alan Rufus who

granted the lands to Abbot Stephen and a group of monks from Whitby. The abbey

church was refounded in 1088 when the King, William

Rufus, visited York in January or February of that year and gave the monks

additional lands.

Within a few decades, as many as 40 parish churches

stood within York, giving an indication of its large population. York once more

became an important, bustling commercial city.

Twelfth century

In the 12th century York started to prosper. In

the Middle Ages, York grew as a major wool trading centre and became the

capital of the northern ecclesiastical province of the Church of

England

1190

Under the protection of its sheriff, York had a

substantial Jewish community. In 1190, Clifford’s Tower was the site

of an infamous massacre of its Jewish inhabitants, in which

at least 150 Jews died.

1212

The city, through its location on the River Ouse and its proximity to the Great North Road,

became a major trading centre. King John granted the city's

first charter in 1212, confirming trading rights in England and

Europe. The city was no longer controlled by a sheriff,

but headed by a mayor elected by the citizens.

During the later Middle Ages, York merchants imported

wine from France, cloth, wax, canvas, and oats from the Low Countries,

timber and furs from the Baltic and exported grain

to Gascony and grain and wool to the Low Countries.

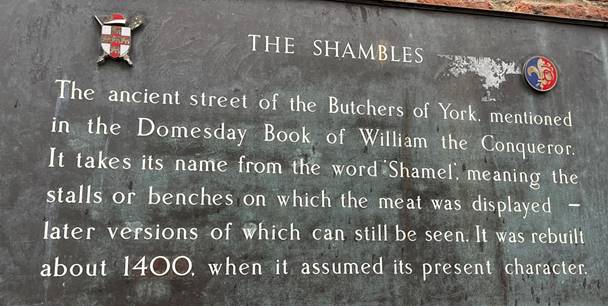

The Shambles was originally a street for butchers, and

you can still see outdoor shelves and hooks on which meat was hung.

York became a major cloth manufacturing and trading

centre. Edward I further stimulated the city's economy by using the

city as a base for his war in Scotland.

1226

In 1226 work started on the construction of York’s

town walls.

1298

Royal government relocated to York during the Scottish

Wars.

Clifford’s Tower housed the royal treasury.

1381

The city was the location of significant unrest during

the so-called Peasants' Revolt in 1381.

1396

The city acquired an increasing degree of autonomy

from central government including the privileges granted by a charter

of Richard II in 1396. The timber-framed Merchant Adventurers’ Hall,

built in the mid-14th century, is a remnant of that era.

Fifteenth Century

York’s economy began to decline towards the later

Middle Ages. During the 15th century the city fathers attempted to maintain its

image, building a new guildhall and St Williams College (as accommodation for

the Minster’s Chantry priests), both of which still stand today.

1472

York Minster, the largest Gothic cathedral north of

the Alps, was finally completed in 1472.

Yet the cloth industry, the mainstay of the city’s

economy, had gradually moved to other parts of Yorkshire, Halifax, Wakefield,

Leeds, where trade was less strictly controlled and regulated. The population

fell, houses were abandoned.

1536

The city underwent a period of economic decline

during Tudor times. Under King Henry VIII, the Dissolution

of the Monasteries saw the end of York's many monastic houses,

including several orders of friars, the hospitals of St Nicholas and of St

Leonard, the largest such institution in the north of England.

This led to the Pilgrimage of Grace, an uprising

of northern Catholics in Yorkshire and Lincolnshire opposed to religious

reform. Henry VIII restored his authority by establishing the Council of

the North in York in the dissolved St Mary's Abbey. The city became a

trading and service centre during this period. The

reestablishment of the King’s Council in the North,

turned York again into a major administrative and judicial centre.

1561

Under Elizabeth I, the High Commission Court for the

Northern Province of York was established in 1561. The Council and Court

together brought government institutions to the city and, as

a consequence, attracted large numbers of people who needed to be fed,

housed and provided with the basics of daily living. This brought renewed trade

into the city, along with a gentry who demanded luxury goods.

Yorkshire cloth was once more in demand, along with

sheepskin, in part to support the quantity of parchment required for the documentation

by the Council and Court. By the end of the 16th century, York was bustling

once again, with more than 60 inns housing and feeding visitors and merchants.

1605

Guy Fawkes, who was born and educated in York, was a

member of a group of Roman Catholic restorationists that planned

the Gunpowder Plot. Its aim was to displace Protestant rule

by blowing up the Houses of Parliament while King James I, the entire Protestant, and even most

of the Catholic aristocracy and nobility were inside.

1642

During the Civil War, in 1642, Charles I fled London

and set up court in York for several months, making it effectively the national

capital. Even after his departure, it remained a

royalist stronghold, and was besieged and eventually captured by the

parliamentarians.

1644

In 1644, during the Civil War,

the Parliamentarians besieged York,

and many medieval houses outside the city walls were lost.

The barbican at Walmgate Bar was undermined

and explosives laid, but, the plot was discovered.

On the arrival of Prince Rupert, with an army of

15,000 men, the siege was lifted. The Parliamentarians retreated some

10 km from York with Rupert in pursuit, before turning on his army and

soundly defeating it at the Battle of Marston Moor. Of Rupert's

15,000 troops, no fewer than 4,000 were killed and 1,500 captured. The

siege was renewed; the city could not hold out for much longer,

and surrendered to Sir Thomas Fairfax on 15 July.

1660

Following the restoration of the monarchy in

1660, and the removal of the garrison from York in 1688, the city was dominated

by the gentry and merchants, although the clergy were still important.

Competition from Leeds and Hull,

together with silting of the River Ouse, resulted in

York losing its pre-eminent position as a trading centre but the city's role as

the social and cultural centre for wealthy northerners was on the rise.

York's many elegant townhouses, such as

the Lord Mayor's Mansion House and Fairfax House date from

this period, as do the Assembly Rooms, the Theatre Royal, and

the racecourse.

During this general time period,

the American city of New York and the colony that contained

it were renamed after the Duke of York (later King James II).

1839

The railway promoter George Hudson was

responsible for bringing the railway to York in 1839. Although Hudson's career

as a railway entrepreneur ended in disgrace and bankruptcy, his promotion of

York over Leeds, and of his own railway company (the York and North

Midland Railway), helped establish York as a major railway centre by the late

19th century.

The introduction of the railways established

engineering in the city.

At the turn of the 20th century, the railway

accommodated the headquarters and works of the North

Eastern Railway, which employed more than 5,500 people.

1862

The railway was instrumental in the expansion

of Rowntree's Cocoa Works. It was founded in 1862 by Henry Isaac Rowntree,

who was joined in 1869 by his brother the

philanthropist Joseph. Another chocolate manufacturer, Terry's

of York, was a major employer.

1900

By 1900, the railways and confectionery had become the

city's two major industries.

1942

In the Second World War, York was bombed as part

of the Baedeker Blitz. Although less affected by bombing than other

northern cities, several historic buildings were gutted

and restoration efforts continued into the 1960s.

Links, texts and books

Victoria County History – Yorkshire, A History of the

County of York: the City of York, 1961.

Seebohm Rowntree, Poverty, A Study of Town Life, 1901

which studied poverty in York.