|

|

Religion

Religion in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in Yorkshire and beyond

|

|

Dates

are in red.

Hyperlinks

to other pages are in dark

blue.

Headlines

are in brown.

References

and citations are in turquoise.

Contextual

history is in purple.

This webpage about the Redcar has the following section headings:

- The Farndales of Religion

- Making sense of the world

- Religion in the fifteenth and sixteenth

centuries

- Church of England

- Catholic Church

- Ther Methodists

- Primitive Methodism

- Temperance

See also the

historical context of the evolution of the

Church.

The Farndales and Religion

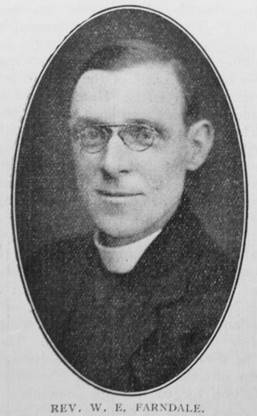

William

Farndale (FAR00435)

was a goods porter, who by 1881 was a Methodist local preacher on the railways.

He led Primitive Methodist Camp Meetings. By 1887 he had moved to Manchester

and became a town missionary in Macclesfield.

William’s son

was Dr William Edward Farndale (FAR00576)

who entered the Primitive Methodist ministry in 1904. He led circuits in

London, Oldham, Chester-le-Street, Birkenhead and Grimsby before he became

President of the Primitive Methodist Conference in 1947. He was particularly

interested in rural methodism and led a “Back to the Soil” campaign.

The Methodism in

Cleveland, The Methodist Recorder 17 April 1902 described local methodism and the prominent

role of Charles Farndale (FAR00341)‘s

family: … For very

many years services have been held in the spacious farm kitchen of Mr C

Farndale, Kilton lodge, which was also that of his father before him.

Methodism in the neighbourhood and the cause of righteousness generally owes

much to the high Christian character and active interest in all good works

displayed by this devoted Methodist family. Here the preachers have always

found a hearty welcome and ministers and others who know the circuit spent

under this hospitable roof.

When his son George

Farndale (FAR00540)

retired from farming in 1940, the Daily Gazette for Middlesbrough, 8 March 1940 reported: For over a century the Farndale

family have been associated with the Loftus and Staithes Wesleyan Circuit, a

connection which is soon to be severed by the removal of Mr George Farndale

from Kilton Lodge to Saltburn. A member of the third generation

of the well known family, Mr Farndale has been a circuit official for over 20

years, and a steward for seven. His grand father was a local preacher in

the circuit for a number of years, and the late Charles Farndale

upheld the family tradition by serving for the major period of his life as

circuit official and steward. In the outlying districts of the circuit Mr

George Farndale has worked equally hard, and stands as Trustee for many of

the circuit chapels.

Making sense of the World

As our

ancestors devoted every hour to grunt and sweat under a weary life,

religion helped them to make sense of the world. They faced the dread of poverty and daily worries about survival. Inevitably

they would have hoped for something better, but would have dreaded what might

happen next. William Shakespeare, Hamlet: For

who would bear the whips and scorns of time, The oppressor's wrong, the proud

man's contumely, The pangs of despised love, the law's delay, The insolence of

office and the spurns That patient merit of the unworthy takes, When he himself

might his quietus make With a bare bodkin? who would fardels bear, To grunt and

sweat under a weary life, But that the dread of something after death, The

undiscover'd country from whose bourn No traveller returns, puzzles the

will And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of? Thus conscience does make cowards of us

all; And thus the native hue of resolution Is sicklied o'er with the pale cast

of thought, And enterprises of great pith and moment With this regard their

currents turn awry, And lose the name of action.

Hamlet’s

soliloquy recognised the worries of the unknown might makes us rather bear

those ills we have and plough on with life.

Religion in the fifteenth

and sixteenth centuries

People in the

middle ages believed that, after death, the soul spent a certain length of time

in Purgatory and that the prayers of the living hastened the soul’s passage to

Paradise.

Rich people

built almshouses where poor people were cared for. In return, those who relied

on this charity had to attend daily Catholic masses, religious services where

they said prayers especially for their benefactors.

There were many

people in medieval England who, while not having the wealth of the landed

gentry to pay for such chantries, had become relatively rich through trade and

they formed religious guilds to ensure a less painful progress to Heaven. The

amount paid to the Skelton priest is recorded for 1527: “St Mary Gild – Robert

Westland, husbandman of the parish of All Saints: 13s 4d”

The seventeenth century

The Act of Uniformity 1662 prescribed the form of

public prayers, administration of sacraments, and other rites of the

Established Church of England and “for preventing mischiefs and dangers that

may arise by certain persons called Quakers, and others refusing to take oaths.”

The Act declared it “altogether unlawful and contrary to the word of God”

to refuse to take an oath, or to persuade another person to refuse to do so. It

further made it “an offense for more than five persons, commonly called

Quakers. to assemble in any place under pretense of joining in a religious

worship not authorized by the laws of this realm.”

Nineteenth Century

Victorian

Britain was a highly religious society. The most reads books were the Bible and

Pilgrim’s Progress.

The 1851

census:

·

A

relatively high 5.3M people neglected religious services, 29% of the

population.

·

But

7.3M attended church, 41% of the population.

·

Morte

than half of the attendances were to Nonconformist chapels.

There had been

an explosion of New Dissent groups, particularly methodists from the 1770s.

The Old Dissent

– Presbyterians, Congregationalists, Baptists, Quakers

The New Dissent

– Methodists

The Church of

England remained the largest religious body, withy 85% of marriages in 1851

being in churches. The Church of England continued to play a key role in

information, education, welfare, judicial and local government issues.

(Robert Tombs, The English and their History, 2023,

459 to 464).

Twentieth century

The inter war

years saw a gradual decline in institutional religion, especially

nonconformity.

Religious belief were challenged by new

geological, archaeological and astronomical discoveries.

Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology (1830 to

1833).

Robert

Chambers’

Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1844)

Charles

Darwin’s

On the Origin of

Species by Natural Selection

was largely written after the HMS Beagle voyage in the 1830s, under Malthus’

influence but publication was delayed until 1859.

Samuel Smiles’ Self Help.

These all had implications for theories

of divine creation and led to a clash with the Church at a meeting of the

British Association of Oxford in 1860 between Thomas Henry Huxley, defending Darwin and “Soapy

Sam” Wilberforce,

son of the anti slavery campaigner, William Wilberforce, Bishop of Oxford. The

Evangelical literal interpretation of the Bible was particularly threatened.

See the Kirkdale cave discoveries.

There was a religious response by

building churches and chapels at scale, with networks of charities, sports

clubs and Bible study groups.

Church of England

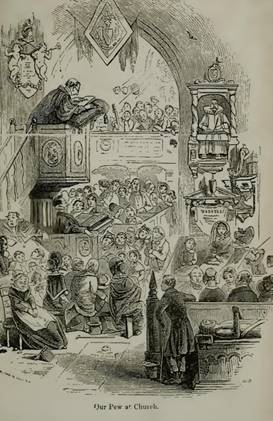

Our Pew at the Church, Charles Dickens, Pickwick Papers, Chapter 2

Here is our pew in the church. What a

high-backed pew! With a window near it, out of which our house can be seen, and

IS seen many times during the morning’s service, by Peggotty, who likes to make

herself as sure as she can that it’s not being robbed, or is not in flames. But

though Peggotty’s eye wanders, she is much offended if mine does, and frowns to

me, as I stand upon the seat, that I am to look at the clergyman. But I can’t

always look at him—I know him without that white thing on, and I am afraid of

his wondering why I stare so, and perhaps stopping the service to inquire—and

what am I to do?

Lark Rise, Flora Thomson,

Chapter XIV, To Church on Sunday: If the Lark Rise people had been asked

their religion, the answer of nine out of ten would have been 'Church of

England', for practically all of them were christened, married, and buried

as such, although, in adult life, few went to church between the baptisms of

their offspring. Every Sunday, morning and afternoon, the two cracked,

flat-toned bells at the church in the mother village called the faithful

to worship. Ding-dong, Ding-dong, Ding-dong, they went, and, when they

heard them, the hamlet churchgoers hurried across fields and over stiles, for

the Parish Clerk was always threatening to lock the church door when the bells

stopped and those outside might stop outside for all he cared. The interior was

almost as bare as a barn, with its grey, roughcast walls, plain-glass windows,

and flagstone floor.

The Parish

Clerk

Lark

Rise, Flora Thomson, Chapter XIV, To Church on Sunday: The Parish Clerk at the back to

keep order. 'Clerk Tom', as he was called, was an important man in the

parish. Not only did he dig the graves, record the banns of

marriage, take the chill off the water for winter baptisms, and stoke the

coke stove which stood in the nave at the end of his seat; but he also took an

active and official part in the services. It was his duty to lead the

congregation in the responses and to intone the 'Amens'. The psalms were

not sung or chanted, but read, verse and verse about, by the Rector and people,

and in these especially Tom's voice so drowned the subdued murmur of his

fellow worshippers that it sounded like a duet between him and the clergyman.

Sermons

Lark

Rise, Flora Thomson, Chapter XIV, To Church on Sunday: Mr. Ellison in the pulpit was the

Mr. Ellison of the Scripture lessons, plus a white surplice. To him, his

congregation were but children of a larger growth, and he preached as he

taught. Another favourite subject was the supreme rightness of the social order

as it then existed. God, in His infinite wisdom, had appointed a place for

every man, woman, and child on this earth and it was their bounden duty to

remain contentedly in their niches.

Rector’s

visits

Lark

Rise, Flora Thomson, Chapter XIV, To Church on Sunday: The Rector visited each cottage in

turn, working his way conscientiously round the hamlet from door to door, so

that by the end of the year he had called upon everybody. When he tapped

with his gold-headed cane at a cottage door there would come a sound of

scuffling within, as unseemly objects were hustled out of sight, for

the whisper would have gone round that he had been seen getting over the stile

and his knock would have been recognized. The women received him with

respectful tolerance. A chair was dusted with an apron and the doing of

housework or cooking was suspended while his hostess, seated uncomfortably on

the edge of one of her own chairs, waited for him to open the conversation.

When the weather had been discussed, the health of the inmates and absent

children inquired about, and the progress of the pig and the prospect of the

allotment crops, there came an awkward pause, during which both

racked their brains to find something to talk about. There was nothing. The

Rector never mentioned religion. That was looked upon in the parish as one of

his chief virtues, but it limited the possible topics of conversation. Apart

from his autocratic ideas, he was a kindly man, and he had come to pay a

friendly call, hoping, no doubt, to get to know and to understand his

parishioners better. But the gulf between them was too wide; neither he nor his

hostess could bridge it. The kindly inquiries made and answered, they had

nothing more to say to each other, and, after much 'ah-ing' and 'er-ing', he

would rise from his seat, and be shown out with alacrity.

Catholic Church

Lark

Rise, Flora Thomson, Chapter XIV, To Church on Sunday: The Catholic minority at the inn

was treated with respect, for a landlord could do no wrong, especially

the landlord of a free house where such excellent beer was on tap. On

Catholicism at large, the Lark Rise people looked with contemptuous

intolerance, for they regarded it as a kind of heathenism, and what excuse

could there be for that in a Christian country? When, early in life, the end

house children asked what Roman Catholics were, they were told they were 'folks

as prays to images', and further inquiries elicited the information that they

also worshipped the Pope, a bad old man, some said in league with the Devil.

Their genuflexions in church and their 'playin' wi' beads' were described as 'monkey

tricks'.

The Methodists

The Enlightenment which

emerged after the Glorious Revolution was also a time of religious revival.

This new evangelicalism was profoundly different from the Puritanism that

dominated the Civil War period.

It emerged from the Oxford

undergraduates in the 1730s, particularly John Welsey and George Whitefield.

Wesley wrote more prolifically than anyone else in the eighteenth century. He

was influenced by Locke’s

philosophy to develop a practical

method (hence methodism) of piety. It grew out of the forces of the

Enlightenment. It also grew within the existing Church and found impetus in

areas of rapid change, including rural areas of the north of England and Wales,

especially in industrial towns. It attracted miners, sailors and soldiers and

others. This is why there was an emphasis on travelling preachers who gave open

air services. It also had a strong women’s movement as it gave a unique for the

time important role to women. Singing was an important part of methodism. The

Wesley brothers (John and Charles) produced 30 hymn books and composed well

known hymns including Hark the Herald Angels Sing.

Methodism was not suppressed

by the Church. It was both subversive and conservative.

From the 1750s the north,

Wales and the Scottish borders boomed in population and many became integrated

into non conformist sects, especially methodism. John Wesley’s flexible

approach thrived on socio economic change,. An autonomous religious movement

grew around chapels, Sunday schools.

Mainstream methodists

attracted hard working and prosperous businessmen who were now able to vote.

In the Victorian era, Non

conformist, generally Liberal religion thrived in the north, the south west and

the industrial Midlands. It tended to be less agricultural and it formed a peripheral

nationalism with a distinct character.

The non conformists opposed

the public subsidy of church schools under the Education Act 1870 as they

worried that future generations would be brought up Tory and Anglican.

(Robert Tombs, The English and their History, 2023,

286 to 287, 460 to 463).

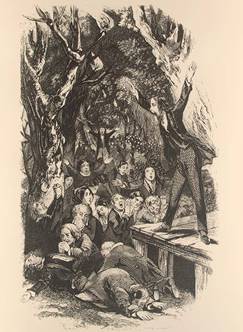

Lark

Rise, Flora Thomson, Chapter XIV, To Church on Sunday: The Methodists were a class apart. Provided

they did not attempt to convert others, religion in them was tolerated.

Every Sunday evening they held a service in one of their cottages, and,

whenever she could obtain permission at home, it was Laura's delight to attend.

This was not because the service appealed to her; she really preferred

the church service; but because Sunday evening at home was a trying time,

with the whole family huddled round the fire and Father reading and no one

allowed to speak and barely to move. The first thing that would have struck any

one less accustomed to the place was its marvellous cleanliness. The

cottage walls were whitewashed and always fresh and clean. The man of the house

stood in the doorway to welcome each arrival with a handshake and a whispered

'God bless you!' If the visiting preacher happened to be late, which he

often was with a long distance to cover on foot, the host would give out a hymn

from Sankey and Moody's Hymn-Book, Sometimes a brother or a sister would

stand up to 'testify', and then the children opened their eyes and ears,

for a misspent youth was the conventional prelude to conversion and who

knew what exciting transgressions might not be revealed. Most of them did

not amount to much. One would say that before he 'found the Lord' he had been

'a regular beastly drunkard'; but it turned out that he had only taken a pint

too much once or twice at a village feast. One man, especially, claimed that

pre-eminence. 'I wer' the chief of sinners,' he would cry; 'a real bad lot,

a Devil's disciple. Cursing and swearing, drinking and drabbing, there were

nothing bad as I didn't do. Why, would you believe it, in my sinful pride, I

sinned against the Holy Ghost. Aye, that I did,' and the awed silence would be

broken by the groans and 'God have mercy's of his hearers while he looked round

to observe the effect of his confession before relating how he 'came to the

Lord'. But the chief interest centred in the travelling preacher, especially if

he were a stranger who had not been there before. Then there was the elderly

man who chose for his text: 'I will sweep them off the face of the earth with

the besom of destruction', and proceeded to take each word of his text as a

heading. 'I will sweep them off the face of the earth. I will sweep them off

the face of the earth. I will sweep them off the face of the earth', and so on.

Methodism, as known and practised there, was a poor people's religion,

simple and crude.

In our time

podcast on John Wesley.

The Methodists

offered something people wanted that was not offered by the Anglican Church.

The new preachers showed a passion for the souls and many who responded felt a

strong sense of sin.

Primitive Methodism

Also known as ‘Ranters’, for their enthusiastic preaching,

‘Primitive’ Methodists were so called because they wanted a return to an

earlier, purer form of Methodism, as founded by John Wesley, based on the early

church. In 1932 Primitive Methodists joined with Wesleyan and United Methodists

to form the Methodist Church.

In the early decades of the nineteenth century there was a growing

body of opinion among the Wesleyans that their religion was moving in

directions which were a distortion, even a betrayal, of what John Wesley’s

teachings.

A Methodist preacher called Hugh Bourne became the catalyst for a

breakaway, to form the Primitive Methodists. Their badge of 'primitive' was

used to stress their belief that they were the true guardians of the original,

or primitive, form of Methodism.

The nineteenth century

working class movement known as Primitive Methodism, originated in the

Potteries, where an open air ‘camp’ meeting was held at Mow Cop in 1807,

igniting a passion for the ‘love of God’ which quickly spread across the

Midlands. By the end of the century there were over 200,000 members.

The sorts of issues which divided the Primitives and the Wesleyans

might be summarised:

|

Methodists |

Primitive Methodists |

|

Developed a high doctrine of the Pastoral Office to justify

leadership being in the hands of the ministers. |

Focused attention on the role of lay people. |

|

Were open to cultural enrichment from the Anglican tradition and

more ornate buildings. |

Stressed simplicity in their chapels and their worship. |

|

Were involved with more affluent and influential urban classes. |

Concentrated their mission on the rural poor. |

|

Were nervous of direct political engagement. |

Stressed the political implications of their Christian

discipleship. |

In the context of the

growing democratisation and sense of dislocation caused by the Industrial

Revolution, Primitive Methodism appealed primarily to miners and mill hands,

farm labourers, and workers in developing factory towns. In rural areas,

Primitive Methodists often came into conflict with the Squire and Anglican

clergy, who saw them as a threat to the established order.

The conviction that God’s

love was for all, led to a concern for social justice, and many Primitive

Methodists became involved in politics, as trade unionist leaders, Chartists,

and later as Labour MPs.

George Edwards, who

championed the cause of farm labourers in Norfolk, is typical of the early

trade union leaders who developed their passion and leadership skills through

the Primitive Methodist Chapels. He started his working life at the age of six,

he was illiterate until he became involved in Primitive Methodism and he

embarked on a journey of self-education, as he recounts in From Crow Scaring

to Parliament.

By the end of the 19th century these two streams of Methodism realised

they had more in common than they might have supposed. So conversations began

which led to their being the two principal partners in the union to form the

present-day Methodist Church in 1932.

In 1865 the Skelton Primitive Methodist Church

was built on Green Road. The Primitive Methodists in Skelton had previously

been meeting in local rooms. The movement was by then 50 years old. It was

started by a person called Hugh Bourne, who was born in 1772 at Stoke. He built

his own church 1811 and sent out evangelists. Within thirty years he had

100,000 followers and 1,000 churches. They were popularly known as the

“Ranters”. “Primitive” to them meant, original, getting back to the real

beginnings of whatever they believed in. John Thomas Wharton of Skelton Castle,

being a strong adherent to the Anglican Church, disapproved of them. At first

he refused to let them have the land on which to build their own Chapel. He

finally relented and sold it to them at a high price. A newspaper of the time

reported that one of the Primitive Church members made 30,000 bricks for the

structure, working after his normal daily stint at work. His employer provided

the clay and means of leading them to the site.

Quakers and Unitarians

Smaller sects like to Quakers and Unitarians were adopted by urban

and business elites. The Quakers included Cadbury, Fry, Rowntree, Barclay,

Lloyd, Swan and Hunter, Price and Waterhouse,

Evangelism

Evangelism created charities and philanthropic lobby groups.

Temperance and social

influence

The non

conformist conscience extended to political action and law enforcement to

promote its moral code. William Wilberforce’s influence extended beyond anti

slavery to animal protection and religious education. The John Keble’s Oxford

Movement in the 1820s was a High Church revolt against Anglicanism.

Religious life

in Britain thus became complex, ranging from Roman Catholics (relative to whom

discrimination was largely degraded in 1791 and 1829 reforms) to Mormons.

Halifax had 7

religious buildings in 1801 and 99 in 1901.

By 1901 England

had 34,000 religious buildings, one for every 1,000. Most seats in churches

belonged to specific people or families, so there was an air of exclusivity to

membership.

The temperance

movement obtained regulation of access to drink and alcohol consumption

declined from the 1870s.

Drink was seen

to be at the heart of moral, social and economic problems. In the 1850s

reformers campaigned against beer and ale houses as the direct causes of

crimes. Places of popular entertainment were targeted. Temperance built up a

large organised following focused around churches, chapels and Sunday school.

However drinking culture was also central to social life and there were only

really local successes in the control of drink, although there was a general

decline in drinking in the second half of the nineteenth century. Temperance

measures never came close to those in Wales and US. (Robert

Tombs, The English and their History, 2023, 502).

There is an In

Our Time podcast on the

Temperance Movement.

Charles

Dickens, Hard Times:

Coketown, to

which Messrs. Bounderby and Gradgrind now walked, was a triumph of fact; …

You saw

nothing in Coketown but what was severely workful. If the members of a religious persuasion

built a chapel there—as the members of eighteen religious persuasions had

done—they made it a pious warehouse of red brick, with sometimes (but

this is only in highly ornamental examples) a bell in a birdcage on the top of

it. The solitary exception was the New

Church; a stuccoed edifice with a square steeple over the door, terminating in

four short pinnacles like florid wooden legs.

All the public inscriptions in the town were painted alike, in severe

characters of black and white. The jail

might have been the infirmary, the infirmary might have been the jail, the

town-hall might have been either, or both, or anything else, for anything that

appeared to the contrary in the graces of their construction. Fact, fact, fact, everywhere in the material

aspect of the town; fact, fact, fact, everywhere in the immaterial. The M’Choakumchild school was all fact, and

the school of design was all fact, and the relations between master and man

were all fact, and everything was fact between the lying-in hospital and the

cemetery, and what you couldn’t state in figures, or show to be purchaseable in

the cheapest market and saleable in the dearest, was not, and never should be,

world without end, Amen.

A town so

sacred to fact, and so triumphant in its assertion, of course got on well? Why no, not quite well. No?

Dear me!

No. Coketown did not come out of its own

furnaces, in all respects like gold that had stood the fire. First, the perplexing mystery of the place

was, Who belonged to the eighteen denominations? Because, whoever did, the labouring people

did not. It was very strange to walk

through the streets on a Sunday morning, and note how few of them the barbarous

jangling of bells that was driving the sick and nervous mad, called away from

their own quarter, from their own close rooms, from the corners of their own

streets, where they lounged listlessly, gazing at all the church and chapel

going, as at a thing with which they had no manner of concern. Nor was it merely the stranger who noticed

this, because there was a native organization in Coketown itself, whose members

were to be heard of in the House of Commons every session, indignantly

petitioning for acts of parliament that should make these people religious by

main force. Then came the Teetotal

Society, who complained that these same people would get drunk, and

showed in tabular statements that they did get drunk, and proved at tea

parties that no inducement, human or Divine (except a medal), would induce them

to forego their custom of getting drunk.

Then came the chemist and druggist, with other tabular statements,

showing that when they didn’t get drunk, they took opium. Then came the experienced chaplain of the

jail, with more tabular statements, outdoing all the previous tabular

statements, and showing that the same people would resort to low haunts, hidden

from the public eye, where they heard low singing and saw low dancing, and

mayhap joined in it; and where A. B., aged twenty-four next birthday, and

committed for eighteen months’ solitary, had himself said (not that he had ever

shown himself particularly worthy of belief) his ruin began, as he was

perfectly sure and confident that otherwise he would have been a tip-top moral

specimen. Then came Mr. Gradgrind and

Mr. Bounderby, the two gentlemen at this present moment walking through

Coketown, and both eminently practical, who could, on occasion, furnish more

tabular statements derived from their own personal experience, and illustrated

by cases they had known and seen, from which it clearly appeared—in short, it

was the only clear thing in the case—that these same people were a bad lot

altogether, gentlemen; that do what you would for them they were never thankful

for it, gentlemen; that they were restless, gentlemen; that they never knew

what they wanted; that they lived upon the best, and bought fresh butter; and

insisted on Mocha coffee, and rejected all but prime parts of meat, and yet

were eternally dissatisfied and unmanageable.

In short, it was the moral of the old nursery fable:

There was an

old woman, and what do you think?

She lived

upon nothing but victuals and drink;

Victuals and

drink were the whole of her diet,

And yet this

old woman would NEVER be quiet.